FOUNDATIONS: Safeguarding Adolescents in London (SAIL)

Safeguarding Adolescents in London (SAIL) describes the principles and practice that, as statutory safeguarding partners, we believe should underpin the work of agencies in London.

Navigate SAIL

Topics in this Section

Foreword and Introduction by Florence Kroll CBE, Chair of the Association of London Directors of Children’s Services (ALDCS) and Chair of the London Adolescent Safeguarding Oversight Board (LASOB)

Adolescent safeguarding rightly has a very high profile in London.

We regularly hear about young people who suffer harm and exploitation in the capital. Some tragically lose their lives, often doing so at the hands of other young people. In this context everyone wants to do something. This can create a great deal of activity; a blizzard of initiatives sponsored by multiple local, regional and national bodies. At the end of the line are practitioners who get on with the day-to-day work of building purposeful relationships with young people, helping to navigate the busy adolescent safeguarding systems which are designed to offer protection but which we know can themselves inadvertently be harmful.

It is in this crowded terrain that the London Safeguarding Children’s Executive, working through its Adolescent Safeguarding Oversight Board (LASOB), is seeking to bring greater coherence to the work of partners and practitioners, so that our collective energy is used to greatest effect to help to make the capital safer for our young people. The Safeguarding Adolescents In London (SAIL) guidance is our attempt to bring together the principles and practice that, as statutory safeguarding partners, we believe should underpin the work of agencies in London.

Chair of the Association of London Directors of Children’s Services (ALDCS) and Chair of the London Adolescent Safeguarding Oversight Board (LASOB)

There is already a great deal of effective evidence based practice taking place in London across our partnerships. We are grateful for the generosity of sharing practice so that we can all learn together and continue to ensure we collectively meet the needs of children and young people in London.

Safeguarding Adolescents In London (SAIL) has been produced to promote consistently high-quality practice by those working to keep young people safe in the capital. It seeks to bring together theory, practice and policy to equip practitioners, managers and service leaders with the information and tools they need to develop their practice and enhance the effectiveness of the adolescent safeguarding systems of which they are a part. In doing so we want to be confident that wherever a young person lives, and as they move around the city, they will receive a response which is underpinned by a shared set of principles, evidence informed practice and an understanding of adolescents, their contexts and their lived experience.

This digital resource is by no means an exhaustive account of all aspects of adolescent safeguarding, but it is a platform which we will continue to build upon and further develop as policy and practice matures in relation to adolescent safeguarding. We hope that you find this a valuable resource and that it fulfils its purpose of enhancing our adolescent safeguarding practice and keeping young people safer in London.

Florence Kroll CBE

Chair of the Association of London Directors of Children’s Services (ALDCS) and Chair of the London Adolescent Safeguarding Oversight Board (LASOB)

Purpose of SAIL

This guide has been developed to support those working to promote safety for adolescents in London.

This is both practitioners, working directly with young people and their families, and those managers and senior leaders who are responsible for providing the structures which give young people and those supporting them the best chance of success.

This guide is therefore designed to help you to:

- Build practical skills which will promote effective relational practice

- Enhance your understanding of adolescent development to help inform practice approaches

- Better understand the London context and promote culturally competent and anti-racist practice

- Place your practice within national and regional frameworks, procedures and protocols which define expectations of practitioners and services

- Reflect upon the key elements which need to be present within an adolescent safeguarding system in order to create conducive conditions for practice

- Understand how theory and the evidence base around work with adolescents can inform your practice

- Promote practice which is underpinned by values and a shared set of principles

- Develop systems thinking and an appreciation of how partners in the adolescent safeguarding can contribute to promoting safety and how practitioners can navigate these systems for and with young people

“It’s like an ongoing battle between two generations. Adults think, ‘we’re right, we’re right!’ But what if young people are the ones who are actually evolving? And the more the adults do that, the more the young people separate ourselves from you.’

Quote from a young person

I feel like professionals always want to look at it from one perspective. You could say ‘that’s a number six’, and a young person could stand around the other side of it, and say ‘that’s a number nine’. You have to sometimes put yourself in a young person’s shoes to actually understand and see what’s going on. to relate, to catch up, to like, morph yourself into the situation, and see this safety issue through a young person’s eyes. See how we see the world! It’s so different for us now than it was twenty or even ten years ago.”

Principles underpinning SAIL

SAIL is underpinned by a set of principles which have been shared and agreed through the London Adolescent Safeguarding Oversight Board (LASOB) and in the case of the Tackling Child Exploitation Principles through a process of national sector dialogue.

We have combined the following sources to create an approach which we believe should inform all work to keep young people safe in London. These are

- The Tackling Child Exploitation multi-agency principles

- Working in partnership with parents and families

- Child First principles

- Commitment to racial equity in practice

- Recognition of the impact of social / structural harms on young people’s safety and wellbeing

- Understanding adolescence in the context of social ecological theory

Tackling Child Exploitation (TCE) multi-agency principles

It’s important to be able to articulate what underpins our approach to our work and to strive to establish a shared set of principles, so that practitioners, whichever agency they represent, can have a common understanding of the values that as safeguarding partners we want to work towards.

The Tackling Child Exploitation (TCE) multi-agency principles provide a sound basis for practice, as they have been tested and agreed with practitioners across England. These are, however, explicitly aimed at harm outside the home and the SAIL guidance seeks to safeguard adolescents from both intra and extra-familial harm. We therefore take the TCE principles as our starting point but build on these to look at the opportunities and challenges of working with parents and families and the interplay between safeguarding inside and outside the home.

Principles are the bedrock of practice.

There are eight TCE Practice Principles, which together support a more holistic response to child exploitation and extra-familial harm, characterised by:

SAIL’s section on working with parents, carers and extended families has been designed specifically to complement the TCE principles and ensure there is a sufficient focus in adolescent safeguarding practice on what goes on in the home and how the family network can be engaged to promote safety. This is intended to support practitioners to engage with risks and strengths inside and outside the home, and work at the interface of the two environments.

You may also be interested in exploring the SAIL section on; Working with parents, carers, family and wider networks and Adolescent Harm: Inside and Outside of the Home

Tackling Child Exploitation (TCE) multi-agency principles – Useful Links

The Child First Principles

While the TCE principles include a commitment to “putting children and young people first” the Child First principles originally developed by the Youth Justice Board go further in detailing what it means to practice in a way which is Child First.

While stemming from work with children in the youth justice system, the Child First principles have come to be a shared basis for practice with all children and young people.

The four tenets of Child First are captured in this mnemonic :

- A – As children: Prioritise the best interests of children and recognising their particular needs, capacities, rights and potential. All work is child-focused, developmentally informed, acknowledges structural barriers and meets responsibilities towards children.

- B – Building pro-social identity: Promote children’s individual strengths and capacities to develop their pro-social identity for sustainable desistance, leading to safer communities and fewer victims. All work is constructive and future-focused, built on supportive relationships that empower children to fulfil their potential and make positive contributions to society.

- C – Collaborating with children: Encourage children’s active participation, engagement and wider social inclusion. All work is a meaningful collaboration with children and their carers.

- D – Diverting from stigma: Promote a childhood removed from the justice system, using pre-emptive prevention, diversion and minimal intervention. All work minimises criminogenic stigma from contact with the system.

PowerPoint Presentation YJB guide to Child First

The Child First principles are also relevant to those adolescents who have moved into young adulthood, as explained by Professor Neal Hazel (extract from the London Reducing Criminalisation of Children Looked After and Care Leavers 2025):

‘While the original context for developing the Child First framework was youth justice, its four tenets equally serve to summarise the evidence base for [work with] young adults. In fact, its key understanding for what brings sustainable positive outcomes – building pro-social identity – was developed from research involving both children and young adults’ – Professor Neal Hazel

Structural harm (extract) by Luke Billingham, Youth worker, Hackney Quest & Researcher, Open University

The fundamental premise of ‘structural harm’ is that children and young people’s wellbeing is not only harmed directly by other people – they can also be harmed by institutions, policies, systems and social norms. If we only consider the risks or harms that young people encounter in their interactions and relationships with other people, we miss the ways in which their need fulfilment and subjective wellbeing can be undermined by factors which go beyond the actions of particular individuals.

Examples of structural harms include poverty; systemic or institutional racism, misogyny and disablism; or injurious experiences in the Criminal Justice System, for instance.

You can read the full Structural Harm section in the practice section here.

Racial equity

The TCE principles rightly encourage us to “recognise and challenge inequalities, exclusion and discrimination” but the London context and the outcomes and experience of global majority children, families and communities require us to be explicit in advocating for racial equity across all our services.

The SAIL guidance starts with a recognition that racism and discrimination shape the lives of black and global majority children and families in London. It also asks that all partners should fulfil the requirement of the Lammy Report to either “explain or reform” the disproportionate outcomes experienced by black and global majority children and young people in London.

Evidence of racial disparities in adolescent safeguarding is clear from the data contained in the ‘London context’ section of SAIL. Examples of practice which are culturally sensitive / humble are woven into this guidance and a section has been developed to explicitly capture examples of equity-driven approaches and the impact this can have on disproportionality.

Racial equity – Useful Links

Adolescent safeguarding systems and an ecological approach

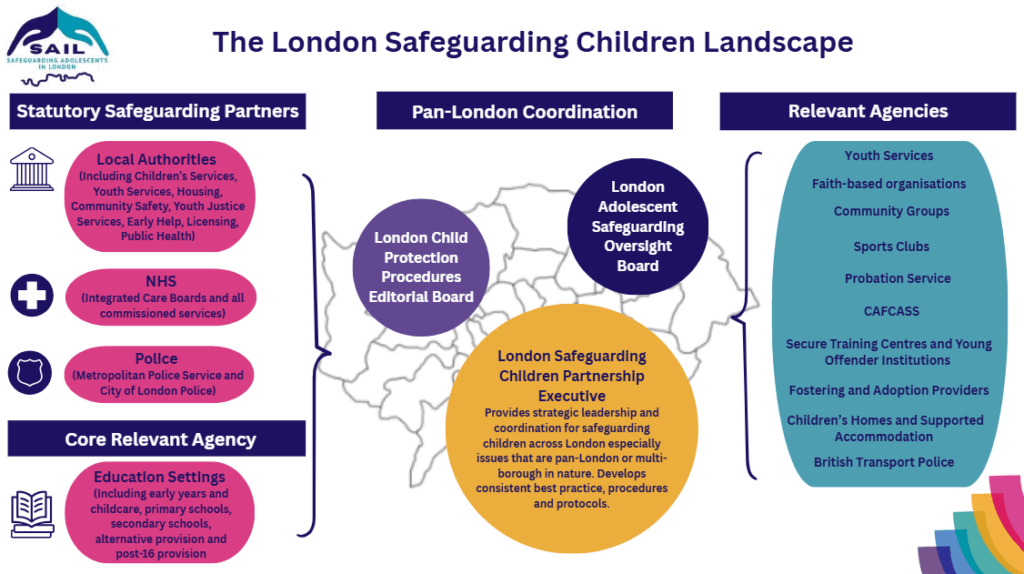

An adolescent safeguarding system is a purposeful multi-agency, multi-disciplinary collaboration and is carried out at the levels of direct relational practice, operational management, strategic leadership, and policymaking.

In London there are clearly defined systems at borough-level and at the pan-London level but we can also describe more localised systems around educational settings, and faith and community venues and structures. Young people and their families operate within and between these locations and how these systems interact contributes to our ability to safeguard them.

The uniting ambitions of adolescent safeguarding systems in London is to create safety and promote well-being of children and young people. This is done through interactions with young people, their peer groups, families, communities, and practitioners, especially those who are affected by risks, harms, abuse, and structural inequalities. It is also done through establishing ways of working between partners and in their interactions with children and young people and their supporters and networks.

Work within an adolescent safeguarding system should always be undertaken in partnership with children and young people, their families and communities.

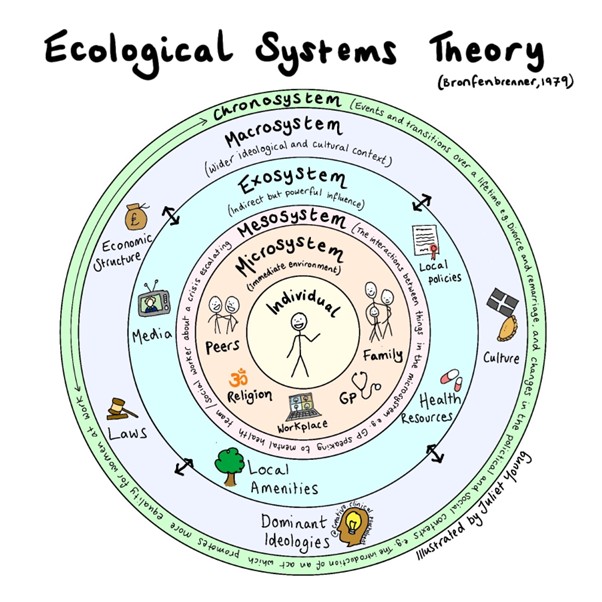

Ecological theory underpins the SAIL guidance and is central to the systemic approaches which inform much of the practice across London’s children’s services. Drawing from the work of Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory views child development as a complex system of relationships affected by multiple levels of influence and interaction with the environment surrounding the child or young person.

The microsystem, the immediate context in which a child develops: home, family, neighbourhood, school and peers is the most influential level but this itself is influenced by the mesosystem which encompasses the interactions of the microsystem eg relationships between parents and school or children and their friendship groups. These systems are themselves shaped by interactions with the wider cultural and economic structures.

Thinking ecologically about adolescent safeguarding helps to place the young person at the centre of the system of people and places, which shape their experience and either promote safety or can undermine it. It recognises how local organisations and practices impact on a young person, or young people, and how these are themselves further shaped by national guidance and laws, and cultural, political and technological changes. Adolescent safeguarding practice has to be alive to these layered systems, while keeping the young person, as a dynamic actor who impacts on their environment, at the centre of their thinking.

Helping practitioners to navigate the adolescent safeguarding system, with and on behalf of the young people and families with whom they work, is a core purpose of this SAIL resource. Helping service leaders to shape those adolescent safeguarding systems, and provide a context which is conducive to relational practice, is another.

Read more about Ecological Systems Theory in the Identify section of the practice section.

Adolescent safeguarding systems and an ecological approach’ – Useful Links

What do we mean by ‘adolescence’?

In SAIL adolescence is used to refer to the phase of growth, development and transition between childhood and adulthood.

The SAIL glossary of terms seeks to define a range of terms as used in this guidance but one term it is important to try to define at the outset is adolescence.

In SAIL adolescence is used to refer to the phase of growth, development and transition between childhood and adulthood.

Adolescence is viewed a distinct and significant stage of human development rather than a fixed age range, however, following the latest research (Orben, Tomova & Blakemore, 2020) adolescence is typically considered to begin at around age 10 and to continue to at least age 24.

Some of the guidance in SAIL is specific to children, recognising the distinct legal status of those under the age of eighteen, however, the principles and much of the practice described is just as relevant to young adults.

It is also important to note that a child’s developmental age may differ from their chronological age. Due to trauma, additional needs or a combination of the two, a child may in some aspects of their personality and interaction present as younger or older than they are ‘on paper’. It is important to acknowledge the impact of biological changes in adolescence may not look the same for all children.

It is, nonetheless, important to recognise that systems for safeguarding young adults are much less well-developed than those for children.

The distinctive challenges of working to safeguard young people post-18 is described in the section on transitional safeguarding

.

The London context

The demographics of safeguarding adolescents in London

London is a diverse community spanning great wealth and poverty across a complex web of ethnicity, class and opportunity.

Safeguarding in such a complicated landscape, within the most densely populated part of England, is rich in challenge.

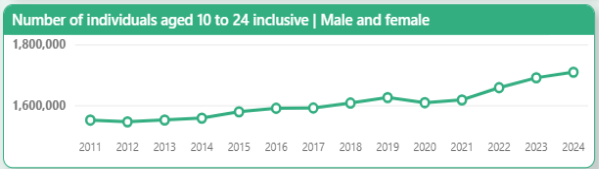

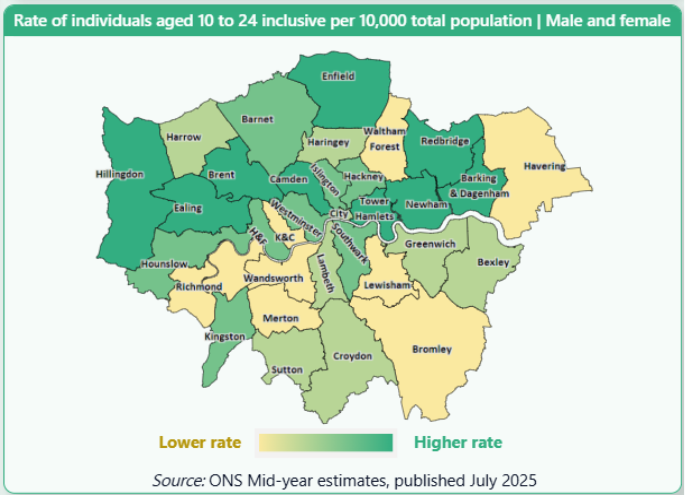

The 10-24 year old population of London has been rising steadily since 2021 according to ONS statistics but it’s distribution across London is quite varied.

The 10-24 rate as a proportion of the total population in each Borough tending to be highest across a West to East axis just above the centre of London.

The rate in the South of London is comparatively lower. However, the size of the adult population affects the rate so it’s important to recognise that Croydon has the fifth largest 10-24 population (72,985) although it has a lower rate than Kingston upon Thames which has the third smallest Borough 10-24 population (33,572).

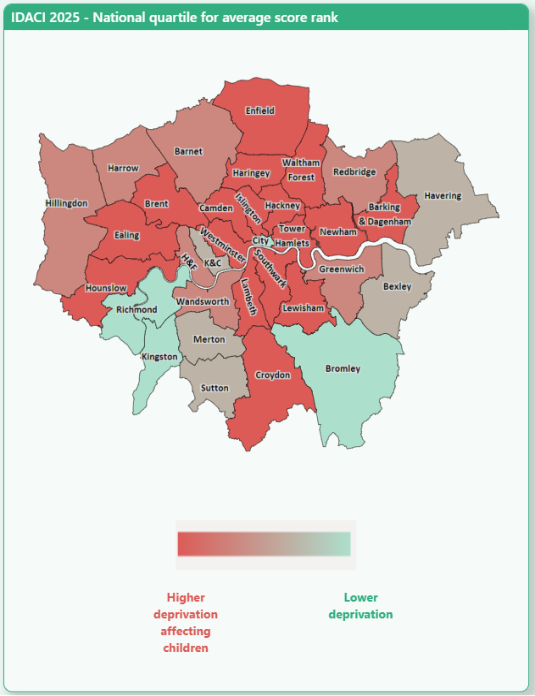

Coupled to this, London is home to children living in some of the most income deprived areas of England. Five of the seven most income deprived areas are in London and of the 32 London Boroughs, over half (17) are in the most income deprived quartile of England.

(taken from the 2025 Income deprivation affecting children index (IDACI) produced by ONS)

North of the Thames, it’s noticeable that many of the Boroughs with the highest 10-25 population rates and levels of deprivation are the same ones.

Intersecting with the rising population and increasing deprivation are language and ethnicity.

The school census paints a picture of the first languages of children growing up in London, many of course who grow up to be bilingual.

The proportions of school children with English as a first language range from 83% in the South East of London (Bromley) to 33% in the North East of London (Newham).

It’s noticeable that the West of London also has lower proportions of school children with English as a first language.

Newham, Tower Hamlets, Barnet and Ealing feature in all three areas highlighted so far;

- High rates of 10-24 population

- High rates of deprivation

- Low rates of English as a first language

The London Metropolitan Police Force covers all of London (with the exception of the City of London which has it’s own police service). Using their statistics enables us to look at some of the crime, violence and legal challenges facing London adolescents (aged 10 to 24 inclusive).

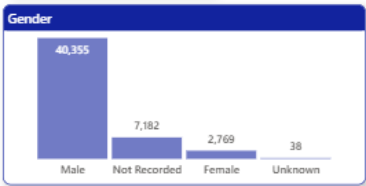

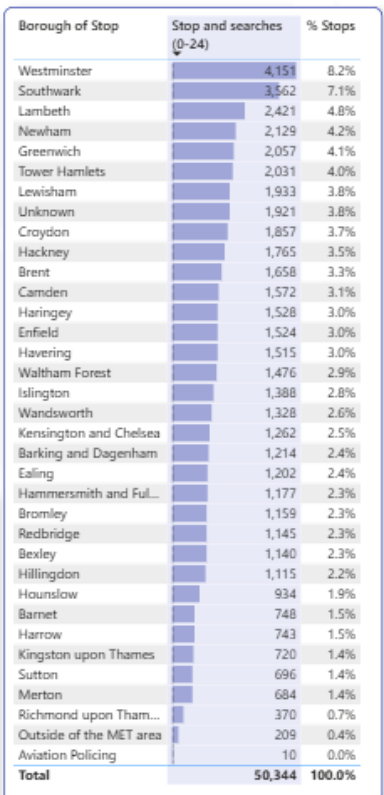

The latest complete calendar year for these stats is 2024. Overall there were 50,344 stop and searches by the Met involving young people aged 0-24 inclusive. In practice, this is nearly always young people aged 10-24 years old.

80% of those stopped were boys and young men.

Westminster was the Borough where the largest number of stops took place in 2024 for this age group. What this doesn’t show us is the home Borough of the young people. Greenwich is the only outer London Borough that features in the top seven stop areas, although it could be argued it’s as much inner London as Newham.

The largest ethnicity group stopped was Black young people, despite being only around 17% of the young London population*. By comparison the white ethnicity group is around 37% of that population.

For both groups 65% of the stops led to no further action but 18% of the black young people were arrested compared to 15% of the white young people.

79% of the 10-14 year olds, 71% of the 15-17 year olds and 60% of the 18-24 year olds stops’ related in no further action.

*Using the school census ethnicity data as a proxy for this group.

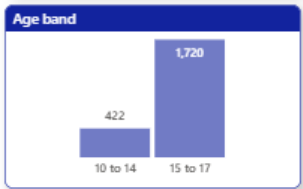

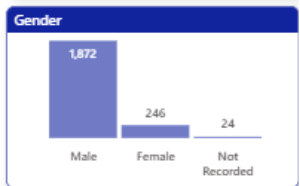

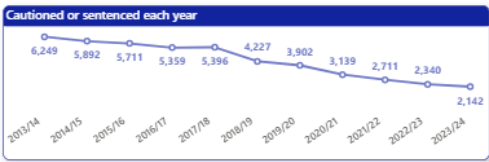

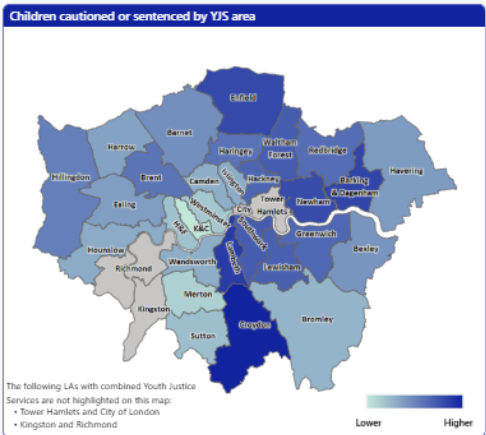

The latest complete year for these statistics is the 2023/2024 financial year. They come from the Youth justice Board. In that year there were 2,142 children aged 10-17 sentenced. A positive thing to note is that this number has been decreasing year on year from 2013/2014.

As in the previous Stop and Search statistics, older children and males make up the largest parts of this group. Black boys are again over represented here, compared to the proportion of the overall population that identify as Black.

The distribution map of the cautions or sentences across London, does have some similarities with the distribution map of income deprivation across London. However, having said that, the numbers here are far smaller and therefore, statistically, we should treat them with greater caution.

Explore regional adolescent safeguarding data and intelligence

You can explore the Adolescent Safeguarding data dashboard via the London Innovation & Improvement Alliance (LIIA) Making Data Speak data insights area.

This dashboard draws on publicly available data to provide a view of data related to the work of the support service, tailored (where possible) to give a London Borough view of the impact within each Borough.

The London safeguarding children landscape

Child safeguarding practice reviews and rapid review assessments

As SAIL evolves we will look to provide a repository for adolescent CSPRs and rapid reviews.

Currently the best distillation of rapid reviews in London is provided by the London Safeguarding Children’s Executive annual analysis. This report looks at themes from all rapid reviews in the capital but does draw out particular areas of interest in relation to adolescent safeguarding.

The report from 2024 can be found here: London-Rapid-Reviews-Analysis-Report-1.pdf

Terminology and usage

Many of the terms used in adolescent safeguarding have overlapping meanings and can often be used interchangeably or interpreted differently across agencies.

In most situations, this overlap does not cause confusion, but there are times when it is important to be precise about meaning, as small differences in terminology can affect how concerns are identified, assessed, and responded to.

For ease of reference and clarity, this section summarises how some related or overlapping terms are commonly used and understood in practice and aims to promote a shared understanding and the consistent use of language across practitioners working with adolescents.

A full glossary of all safeguarding terms can be found in The London Safeguarding Children Procedures (Tri.x). https://trixresources.trixonline.co.uk/glossary

- Child/Young Person/Young Adult/Adolescent

Child

Legally defined under Section 105 of the Children Act 1989 as anyone under the age of 18. Using the term “Child” (as in Child First) keeps our work firmly anchored in the legal and moral reality of safeguarding and youth justice. It challenges the adultification of children and centres their right to protection and care. Contributors to SAIL often use the term ‘child’ to emphasise the legal status of a person under 18 but the term ‘young person’ is also frequently used when this legal precision / emphasis is not essential.

Young Person

A flexible term referring to older children and adolescents, generally aged 10–18 (but sometimes up to 25). It is used to acknowledge growing autonomy and participation while retaining entitlement to protection.

Young Adult

Refers to those aged 18–25 who are legally adults but may still need safeguarding support. Linked to transitional safeguarding approaches acknowledging that vulnerabilities, risks and harm do not stop at the age of 18.

Adolescent

A developmental stage, typically spanning the age range 10–25 years. The term focuses attention on developmental needs and contexts rather than just legal status, recognising that older teenagers and young adults still need safeguarding even when approaching or having reached adulthood.

Risk, Harm and Vulnerability

Risk

Refers to the likelihood that a child or young adult will experience harm. It is forward looking and involves assessing probability and severity of possible harm. In adolescence some risk taking behaviour (e.g. exploring independence, relationships, or identity) is part of normal development so professionals must distinguish between healthy risk-taking and dangerous risk exposure.

Harm

Describes the actual impact or damage to a child’s health or development. The Children Act 1989 defines harm as ill-treatment or impairment of health or development. ‘Significant harm’ is the threshold for statutory protection. Harm may be cumulative and in adolescent safeguarding it may be contextual and emerge through patterns of coercion, peer pressure, or exploitation rather than single incidents. Harm can also be social or structural in nature emanating from factors beyond the child or their family and impacting some children and communities disproportionately,

Vulnerability

Refers to the conditions or factors (e.g. previous life experiences, poverty, disability, social isolation and mental ill health) that make a child or young person less able to protect themselves and more likely to experience harm. Vulnerability can increase the risk of harm but it doesn’t mean a child or young person is unsafe. Overuse of the word vulnerable to describe someone can unintentionally label or stigmatise. In adolescent safeguarding it is important to think of the contexts of vulnerability.

- Adolescent Safeguarding, Harm Outside the Home and Exploitation

Adolescent Safeguarding

Adolescent safeguarding recognises young people experience risk and harm differently from younger children and that their safety is shaped by a combination of intra-familial and extra-familial risks that often interact in complex, overlapping ways.

It understands adolescence as a period of development, autonomy, and identity formation, when young people explore new freedoms, relationships, and social networks. These can be sources of strength and resilience, but they can also create new vulnerabilities or exposure to risk, leading to harm.

Rather than viewing young people solely through a lens of risk or control, adolescent safeguarding focuses on building safety through connection, trust, participation and development. It supports families, communities, and professionals to work with young people to help them navigate challenges and make positive choices.

Harm Outside the Home/Extra-Familial Harm/Exploitation

Harm outside the home is a descriptive umbrella term used to capture any situation where a young person experiences harm beyond their family environment.

It is much broader than exploitation, and includes:

- Community or gang-related violence

- Adolescent relationship abuse

- Peer pressure and coercive group dynamics

- Bullying, harassment, humiliation or exclusion (offline and online)

- Sexual harassment and harmful sexual behaviour

- Peer-on-peer abuse or coercion

- Exploitation (sexual, criminal, labour)

- Radicalisation, violence and extremism

Recognising this breadth helps practitioners see connections between personal, contextual, and structural factors, and to design interventions that target both individuals and environments.

Not all Harm Outside the Home will require a safeguarding response from Local Authority Children’s Services or Youth Justice Services. Bullying or being bullied, as one example, is a form of harm that may be addressed within a school or youth hub, without requiring a referral.

When the impact of harm outside the home reaches the threshold for referral to the Children’s Services front door, the term ‘Extra-Familial Harm’ is used to distinguish it from ‘Inter-Familial Harm’.

Exploitation

Exploitation is a form of harm outside the home and is abuse that almost always entails a person (often an adult, but sometimes peers) takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, control, manipulate or deceive a child or young person into doing something for the exploiter’s benefit.

It is both a form of harm and a process through which harm occurs and is often categorised in three forms:

- Child Sexual Exploitation (CSE) – occurs when sexual activity takes place in exchange for something the child or young person needs or wants (e.g. money, gifts, affection, protection, or status).

- Child Criminal Exploitation (CCE) – involves children being coerced, manipulated, or deceived into criminal activity such as drug supply, theft, or violence (including county lines).

- Labour or Financial Exploitation – though less common, includes forced or unpaid work, coerced begging, or financial control and fraud.

These should not be understood as isolated or siloed categories. Many children and young people experience multiple, overlapping forms of exploitation and other forms of harm outside the home at the same time or move between them as circumstances change.

- Neurodiversity, SEND and other additional needs

Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND)

Identifies a need for educational support under Section 20 of the Children and Families Act 2014 and expanded in the SEND Code of Practice 2015. SEND is an umbrella term about the support needed covering a variety of needs. Some children who require SEND support will have a clinical diagnosis, some children who require SEND support will not have a clinical diagnosis, and conversely some children who have clinical diagnosis will not require SEND support.

Schools and local authorities use the term to decide how to provide resources, adapt teaching and add in additional resources. In lots of cases, schools and colleges are able to do this through existing provision, sometimes however they need to apply to create an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP).

An EHCP is a legal entitlement for children and young people aged up to 25 who need more support than is available through support that would ordinarily be available to all children in mainstream schools. EHCPs identify educational, health and social needs and set out the additional support to meet those needs; this may be provided in either mainstream or specialist settings. Young people however may have SEND without an EHCP. More information about EHCPs can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/children-with-special-educational-needs/extra-SEN-help

Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity is simply at its core the notion that all brains and nervous systems are different. As a term it has been borne from self-advocacy, particularly among autistic self-advocates in the 1990s, and particularly emphasises the concept that specific ‘Neurodivergences’ such as autism, ADHD, or a Learning Disability exist within a much wider spectrum of individual differences we all share to different extents.

More information about Neurodiversity can be found here: https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/identity/autism-and-neurodiversity

Neurodivergent

The term neurodivergent describes an individual whose brain functions in ways that diverge from what society defines as “typical.” It is used to describe differences in thinking, learning, attention, communication, and sensory processing. The term emerged from the neurodiversity movement as a non-medical way to describe cognitive difference in a way that respects and emphasises variation, not deficit.

It is a concept, not a diagnosis, although a diagnosis of a specific condition (e.g. ASD, ADHD, dyslexia or Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) may help to unlock support.

Speech, Language and Communication (SLC) Needs

Taken from the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists:

“The term speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) describes difficulties across one or many aspects of communication including:

- Problems with producing speech sounds accurately

- Stammering

- Voice problems, such as hoarseness and loss of voice

- Problems understanding language (making sense of what people say)

- Problems using language (words and sentences)

- Problems interacting with others. For example, difficulties understanding the non-verbal rules of good communication or using language in different ways to question, clarify or describe things.

Some SLCN are short term and can be addressed through effective early intervention. Others are more permanent and will remain with a person throughout their childhood and adult life.

More information about SLC Needs can be found here: https://councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/files/earlysupportslcnfinal.pdf

Thanks and acknowledgments

SAIL has been, and will continue to be, a labour of love for both the London Innovation & Improvement Alliance (LiiA) editorial team and the myriad contributors who have generated its comprehensive content.

SAIL grew out of the 2022 Adolescent Safeguarding in London practice handbook created by Colin Michel. The evolution from that handbook to the SAIL digital guidance has been made possible by the support of the London Safeguarding Children’s Executive, under the stewardship of Abi Gbago and Ade Adetosoye, and under the steer of the London Adolescent Safeguarding Oversight Board (LASOB).

Thanks should go to all of the LiiA team who have worked on SAIL, with particular recognition to colleagues who have built the digital platform in-house, organised resources, and developed original material. Thanks to Jeanne King, Dr Karla Goodman, Matthew Raleigh, Mei Ho and Rula Tripolitaki.

Thank you also to all who have shared their expertise and time to generate further content, videos and useful resources, as well as to those who have provided feedback to help us to get to a first release of SAIL of which we all can be proud.

SAIL will continue to grow thanks to the ongoing contributions of London’s adolescent safeguarding community. We hope this resource proves its worth as a versatile tool to support practitioners and adds to our collective impact in building safety for London’s children and young people.

Ben Byrne – Director of LiiA

Navigate SAIL

SAIL Disclaimer

SAIL is a collaborative effort. It draws on the work of many researchers, writers, and practitioners across disciplines and perspectives who have generously contributed their time and permitted us to link to their work.

You’re welcome to use and build on these resources but please credit SAIL or the original authors.

We want SAIL to be shaped by its users. We see diversity of perspective underpinned by dialogue and discussion as essential to progress. As a living resource in a rapidly evolving field there will be gaps, variations, and evolving interpretations. Inclusion does not equal endorsement.

We welcome clarifications, corrections, and contributions to keep it growing. Please get in touch using the contact details provided.

Get In Touch with the SAIL Team

SAIL guidance aims to bring together the principles and practice that, as statutory safeguarding partners, we believe should underpin the work of agencies in London. Anything that helps multi-agency practitioners work better with and for adolescents will be included in this digital resource. It will continue to move with the times as new research and evidence of what works continues to emerge.

If you’d like to directly contribute to SAIL then we’d love to hear from you – whether it be providing written content, sharing links to other resources and websites or being part of the ‘Talking Head Series’ – you can read more about the ‘SAIL talking head’ series here!