PRACTICE: Working with adolescents

Adolescence is a time of tremendous potential, growth, change and opportunity, which is why working with adolescents can be hugely rewarding. It requires knowledge, understanding and approaches, which are responsive to this unique and exciting developmental phase.

Navigate SAIL

Topics in this Section

What is adolescence – the stage not an age

Adolescence is the transitional period from childhood to young adulthood, coinciding with puberty, which is a gradual process, taking many years to complete. It is the second most significant phase of development, after infancy (between birth and age 3). There are no hard age definitions to adolescence, and it is recognised that this phase of growing up continues well beyond the age of 18 when many children’s services statutory responsibilities cease.

Adolescence is a distinct and unique developmental phase characterised by significant physical, cognitive and psychosocial changes. It can be a time of considerable risk as adolescents seek to make decisions independent of caregivers and take greater influence from their peers. Neurologically the reward centre of the brain is particularly sensitive, whilst the control centre- responsible for planning, prioritizing and impulse control- is underdeveloped. However, it is also a time of tremendous potential, growth, change and opportunity (WHO 2016), which is why working with adolescents can be hugely rewarding. It requires knowledge, understanding and approaches, which are responsive to this unique and exciting developmental phase.

As with every life stage, young people do not enter into adolescence as a “blank slate”. Even those without a history of involvement with statutory services will have prior experiences and exposures that will influence both biological, psychological and social aspects of their development. However, earlier experience does not necessarily pre-determine how young people progress through adolescence, due to the opportunities for change and reorganisation, through which resilience, recovery and development are possible. Well considered, developmentally appropriate support and scaffolding can help to maximise this opportunity, particularly for those young people who have experienced early adverse experiences. This includes exposure to environments, activities and interactions that bolster opportunities to thrive as young people explore, experiment, learn and grow.

In this section we will consider the developmental characteristics of adolescence and contextual influences to inform, support and enhance your work in helping London’s young people to navigate this opportune stage of development safely and to maximise the opportunities for resilience and growth.

What changes happen during adolescence?

Biological changes

Adolescence coincides with puberty and is marked by a number of physical changes, which include;

- Growth spurts in height, weight and body hair

- Sexual development as genital and reproductive organs mature.

- In females: Breast development and pubic hair growth and the menstruation cycle begins.

- In males: Testes enlargement and descent, voice changes and hair growth

- Skin changes, which can include pimples and acne and body odour

- Changes in hormone levels, required to enable sexual development. The types of hormones released is dependent on the biological sex of the young person and will determine the changes to the body. Intense fluctuations in hormone levels can impact on emotions, mood and behaviour.

The extent, timing and order of changes is unique to each individual. Making sense of what is happening to their bodies can be a time of excitement, uncertainty and/ or distress for young people. Having a trusted person to talk openly with about what is happening for them will help young people to navigate the many physical changes that they will be experiencing. There are helpful resources available to support young people, parents and professionals to understand and make sense of the physical changes that are happening.

Transgender and non-conforming young people may find the changes to their body, particularly distressing and de-stabilising due to the fear or actual development of secondary sexual characteristics that do not align with their gender identity. There are some helpful links for young people here and parents/ carers and professionals here.

Practitioner Note: For whatever reason, you might find it uncomfortable talking with young people about their sexual development. You may, therefore, find it helpful to rehearse some conversations with your peers or supervisors. The more often you lean into the uncomfortable the easier it gets. That way, when you come to talking with young people, you will be better placed to hold any discomfort that they may have.

Biological Changes – Useful Links

- Puberty and your body | Childline

- 24765_Supporting your Child to go through Puberty_4E.pdf

- Worried about your gender identity? Advice for teenagers – NHS

- Think your child might be trans or non-binary? – NHS

- What social workers should consider when working with LGTBQ+ people – Community Care

- https://www.childline.org.uk/info-advice/you-your-body/puberty/puberty-body/#:~:text=Your%20body%20changes%20shape%20during,spots%20or%20acne%20as%20well.

- https://www.barnardos.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-10/24765_Supporting%20your%20Child%20to%20go%20through%20Puberty_4E.pdf

- https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/trans-teenager/

- https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/think-your-child-might-be-trans-or-non-binary/

- https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2022/02/01/what-social-workers-should-consider-when-working-with-lgtbq-people/

Cognitive development

The significant brain changes that occur during adolescence contribute to cognitive developments i.e. the mental processes that take place in the brain such as thinking, learning, memory and perception. This includes developments in;

- Executive functioning skills, which enable effective planning, organising, prioritising, problem solving and impulse control

- Abstract thinking. Moving on from just thinking about concrete facts to allow for thinking about possibilities, allowing for hypothetical and future thinking, considering multiple perspectives and potential solutions

- Mentalisation, which refers to the ability to understand the mental states of the self and others (Fonagy and Allison, 2011). This allows a child to begin to perceive and interpret the intentions and reasons behind the behaviour of others, and therefore to reflect on how other people think, which can help to navigate social relationships, which become increasingly more important (Williamson and Mills, 2022).

- Attention and memory; As the brain becomes more capable of taking on the complex tasks required to process, store and recall memories, the number and strength of memories peak during this life stage. Memories formed during adolescence are most likely to be recalled later in life, which is why every encounter matters for both now and the future.

- Critical thinking and moral reasoning. Young people begin to debate ideas and opinions and form new ideas of their own. They may start to question authority or challenge established societal, moral and political norms and issues. This willingness to question the status quo has meant that adolescents have been at the forefront of social movements for centuries and why involving young people in service design and delivery is critical to support practice improvement and innovation

These cognitive developments do not happen all at once and will develop differently in each individual depending on neurological, psychological, environmental and social influence. Creating opportunities to rehearse and refine these skills will support and nurture these news skills, which enable other aspects of psychosocial development that occur during adolescence.

Young people who have or are exposed to trauma and those who are neurodivergent may display cognitive differences and delay and this should be taken into consideration as you approach your work. The key consideration here is to use the intelligence about young people that exists from their parents and carers, trusted professionals, and of course from the young person themselves; what works for this young person and how should you change your approach?

What can I do to support cognitive development in young people?

- Find creative ways (e.g. song writing, art activities, visits to places of interest) to engage young people in discussion and debates about matters of interest and importance to them

- Encourage participation and contribution to support service design, review and delivery. This could be through advisory groups or opportunities for individual feedback.

- Praise well thought out decisions and reflect together about poorly made or unsafe decisions in a way that is not punitive or judgemental.

- Invite thinking about possibilities for the future. This might include talking through some scenarios [link to What would you do exercise] and encourage them to set and work towards goals.

- Manage expectations of ourselves and others; adolescence is a developmental period- young people will not always get it right, how we respond when they don’t provide an opportunity to support their learning and growth.

- Look to see if there is a communication plan or similar for young people with additional needs or who are neurodivergent, being able to know what works for them in terms of interaction and communication can add significant value.

Social development

Adolescence is a period of significant social change. Developing the skills and knowledge required to become independent is an essential task of adolescence. As young people seek independence from their family and/ or caregivers, peer relationships have greater influence, and they begin to explore romantic relationships and their sexuality.

An important stage of self-discovery begins as young people seek to understand and establish a sense of identity, developing their sense of self including their values, beliefs and goals and their place in their world.

Trusting and consistent relationships with adults are an essential aspect of both social and cognitive development in adolescence.

Peer influence

Social belonging

As the importance of social belonging intensifies and young people navigate new contexts and environments, they start to turn to their peers rather than their parents for companionship, guidance and protection.

A heightened sensitivity to rewards, particularly social rewards, peer acceptance and rejection make young people especially susceptible to peer influence, pressure and exploitation during this transitional period.

Helping young people to understand the potential influence of their peers on their behaviour and equipping them with skills to respond to negative influence. whilst having access to positive influences can help to mitigate risks and build valuable life skills that they can take with them as they transition through to adulthood.

Despite this orientation towards their peers and an increased desire for independence and autonomy, parents and caregivers continue to play an important role in guiding, influencing and keeping young people safe through this complex transition. Secure and supportive relationships with significant adults can provide a safe base through which young people can explore and learn through their new contexts and help to and nurture a positive sense of self. Every child needs an adult that is “irrationally crazy” about them (Bronfenbrenner, 1991). Parenting adolescents brings new challenges and opportunities. Very often parents and caregivers find themselves in need of new tools and perspectives to ensure that they are equipped with the necessary knowledge, skills and support to stay “irrationally crazy” and alongside their teenagers as they navigate this transitional, transformative developmental.

Safeguarding adolescents therefore requires a distinct approach to ensure that risks outside of the home are well considered alongside an understanding of the factors that may push and pull young people from their home and family environments during this transitional period.

Sexuality and romantic relationships

As young people move through adolescence, romantic relationships can become increasingly important and young people may begin to explore their sexuality. This plays an important part in the development of identity as young people begin to shape their personal values towards romance, intimate relationships and their sexuality(Stewart, Spivey, Widman, Choukas‑Bradley, & Prinstein, M. J. (2019) . Romantic relationships provide opportunities to experience emotional intimacy and develop interpersonal skills. Patterns that emerge during this developmental period can impact on the behaviours that are carried into adulthood.

Young people are likely to benefit from support and guidance from trusted adults, to develop interpersonal and regulation skills that can help to manage the new, unfamiliar and often intense social, emotional and sexual experiences that come alongside romantic relationships. For young people who are Neurodivergent, this may come with additional challenges as they cope with both this intense experience alongside a way of seeing the world that may be very different to their peers.

You may also be interested in exploring other related SAIL topics such as: Working with emotions and Appreciating neurodiversity, and considering children with Autism, ADHD and other additional needs or disabilities in your work

Sexually appropriate behaviour

There is a commonly accepted range of sexual behaviours that are considered typical for a child’s age and stage of development. Distinguishing between age-appropriate sexual exploration and potential warning signs of harmful behaviour can be challenging. Waltham Forest provides a helpful tool which may be helpful in setting behaviour within the context of expected sexual development.

If you are concerned about sexually inappropriate behaviour, then there are useful resources on the Lucy Faithful website. The AIM assessment is an evidence-based tool for professionals working with young people, to understand and assess sexually harmful behaviours in order to inform intervention. The AIM project is informed by the Good Lives Model, which offers a strengths-based approach to working with sexually harmful behaviour. There is more information about the Good Lives model here, where you can download a Good Lives plan to find ways to meet needs and set goals for living healthy living.

For children with delayed development or neurodivergence, sexually appropriate behaviour can be something that is challenging to negotiate, as for many people it relies on an understanding of what another person might be feeling through verbal and non-verbal communication. For instance, with some specific neurodivergences such as autism, non-verbal communication can be challenging to understand. It is important however that you do not shy away from addressing concerns, and work with parents, carers and the network around the young person to find what can help them express their sexuality safely.

If you are concerned about a child displaying Harmful Sexual Behaviour and they have additional needs, and specifically a Learning disability, it is recommended that you call the Stop It Now helpline

Sexually appropriate behaviour – Useful Links

https://www.lucyfaithfull.org.uk/advice/concerned-about-a-child-or-young-persons-sexual-behaviour

Concerned about a child or young person’s sexual behaviour – Lucy Faithfull Foundation

The AIM Project – The AIM Project

What is a Good Life and the Good Lives Model? – Shore

https://www.lucyfaithfull.org.uk/our-services/stop-it-now

Identity

Sense of self

A critical task of adolescence is to form a sense of self, a sense of identity through the process of self-exploration and self-discovery. To support a coherent sense of self- that feeling of sameness across different contexts, young people seek and require opportunities to explore different parts of themselves including their values, beliefs and goals. Exploring young people’s values and providing opportunities to align behaviours with these is a core element of the Your Choice Programme. There are some helpful tools taken from the Your Choice Resource pack here. [Link to values section Your Choice Resource Pack]

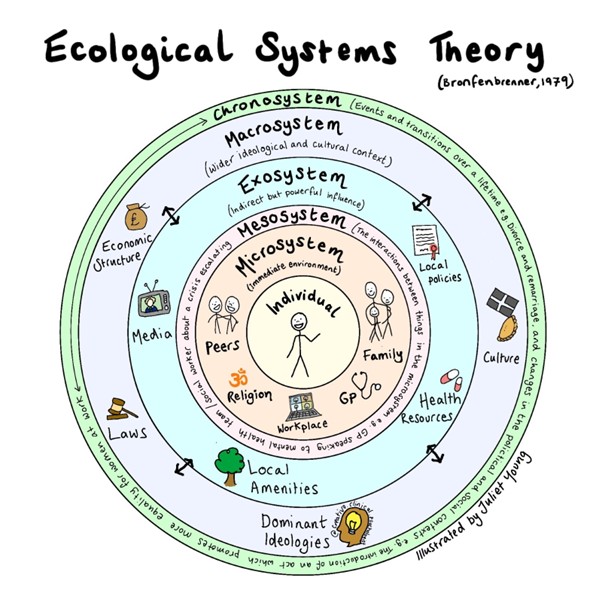

During adolescence young people are particularly sensitive to how they are perceived by others. Each and every encounter therefore provides an important opportunity to influence how the young person views themselves and contributes to the formation of their identity. Indeed, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979) suggests that an individual’s development, including identity formation is shaped by the interactions and relationships between an individual and their environment. According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory there are many interconnected systems, which make up a young person’s environment and it is the interactions between these systems that will influence all aspects of development including the formation of identity.

Specifically, Bronfenbrenner suggest that there are five interrelated systems from immediate relationships to wider societal forces. These systems include;

- The microsystem, which relates to an individual’s immediate environment. This includes someone’s immediate relationships and environments such as parents/ caregivers, siblings and friends.

- The mesosystem, which refers to the interactions between different parts of the microsystem, for example how parents and peers interact and/or how parents and teachers interact.

- The exosystem, which includes the wider social system, which doesn’t necessarily have any direct contact with the young person but influences the young person indirectly by impacting on those they interact with directly. For example, a parent/ caregiver’s workplace may impact on stress and time available for young person. The exosystem also includes local community services such as accessibility and availability of healthcare, parks, youth centres.

- The macrosystem, which encompasses broader societal ideologies, cultural norms, values, laws and government policies. For example, beliefs around gender roles can influence parenting styles and expectations of young person. The macrosystem influences the broader context that affects how all other systems function.

- The chronosystem, which relates to the dimension of time and how this influences development. It considers changes and transitions over time both in an individual’s own life and in the broader environment. For example, the impact of the Covid pandemic was felt across the World and will have impacted on how every individual interacted with all other part of their ecological system. In terms of the chronosystem, the timing of events in an individual’s life (i.e. what else might be happening for them internally in terms of development) and also changes over time are important and impact on other parts of the system.

Exploring alternative identities is considered to be a normal part of the identity formation process. It is therefore important that young people have an opportunity to realise their potential and learn through this developmental process, in a way that is not labelling, stigmatising or assumes a fixed pattern of behaviour.

Child First principles encourages individuals and organisations to respond to young people in a way that acknowledges their developmental stage and recognises their particular needs, capacities, rights and potential. Child First principles are guiding principles which originated from the youth justice system but are usefully applied in other aspects of adolescent safeguarding and family work. There are four guiding principles set out on the YJB website which inform a child first approach to working with young people;

- As children – prioritising the best interests of children and recognising their particular needs, capacities, rights and potential. All work is child- focused, developmentally informed, acknowledges structural barriers and meets responsibilities towards children

- Building pro social identity – promote children’s individual strengths and capacities to develop their pro- social identity for sustainable desistance, leading to safer communities and fewer victims. All work is constructive and future-focused, built on supportive relationships that empower children to fulfil their potential and make positive contributions to society.

- Collaborating with children – encourage children’s active participation, engagement and wider social inclusion. All work is meaningful collaboration with children and their carers.

- Diverting from stigma – promote a childhood removed from the justice system, using pre-emptive prevention, diversion and minimal intervention. All work minimises criminogenic stigma from contact with the system.

In applying and embedding these principles in your practice you are creating opportunities to nurture and re-enforce pro social aspects of a young person’s identity. At the same time acknowledging and responding to the developmental differences of children and young people, allows for the consideration of whole child opportunities for realising their potential.

Sense of Self – Useful Links

SOCIAL GRACES

Social graces is a mnemonic developed by Roper-Hall and Burnham, which provides a useful scaffold to consider less visible and unvoiced aspects that influence personal and social identity.

The Social GGRRAAACCEEESS are; Gender, Geography, Race, Religion, Age, Ability (Physical, Intellectual, Social & Emotional), Appearance, Class, Culture, Ethnicity, Education, Employment, Sexuality (orientation & Expression), Spirituality.

Exploring the different elements that contribute to identity and the intersection between these can help to understand and build on aspects that are important to a young person and to understand how their graces may impact on their own thoughts, feelings and actions and that of others. As a starting point you could ask a young person and/or their family to rank each of the Social Graces in order of importance to them and seek opportunities for connecting and building on aspects most important to them.

Considering how social graces have impacted on their interactions with the world can provide an important opportunity to uncover experiences of inequalities, exclusion and discrimination.

As well as using the social graces to support an understanding of those individuals and families that we work with, understanding one’s own social graces can help to explore and identify power differentials to identify our own prejudice and privilege, which may be impacting on our work. Through Your Choice clinical supervision, practitioners are supported to consider the similarities and differences in social graces with the families that they are working with, to consider how this may be impacting on their work.

Research in Practice provide some useful exercises and activities, which you can use to explore social GRACES within your teams and in supervision discussions

Gender identity

Gender identity is different to sexual identity. Whilst sexual identity refers to who an individual is attracted to, gender identity is how someone describes their gender.

Gender identity is not the same as biological sex. Sex refers to physical and biological traits—such as genitals, hormones, and other body characteristics. At birth, a child’s sex is usually assigned based on these traits. However, a person’s gender identity may not align with the sex they were assigned at birth.

There are many ways in which someone may describe their gender. The most common terms are;

- Cisgender, which refers to someone who is the same gender as their sex

- Transgender, which refers to someone whose gender is different from their sex at birth

- Non binary, non-conforming, gender queer, gender fluid, which are gender identities that sit within, outside of, across or between male and female (Young minds, 2025)

Pronouns are the terms that we use to refer to someone as he/she/they. It is good practice to ask which pronouns young people use to describe themselves and refer to them in accordance with their preference. The pronoun “they” is a gender-neutral pronoun and may be used for people who are non-conforming or transgender. It may be important for you and helpful for young people to share your own pronouns.

The changes to the body that happen during adolescence can be particularly confusing and/or distressing for non-conforming and transgender young people, who are also more likely to experience injustice and discrimination, which can negatively impact on their mental health. A recent ruling by the Supreme Court, defined that within the Equality Act 2010 the legal definition of sex is biologically determined. Under the Equalities Act this means that;

- A woman is a biological woman or girl (a person born female)

- A man is a biological man or boy (a person born male)

This ruling has led to mixed responses, demonstrating that there is not agreement across society about how we define and respond to people who do not consider their gender to be defined according to biological determinants. It therefore seems more important than ever to ensure that young people who are exploring their gender identity have access to appropriate support and access to inclusive environments. There are some useful good practice guides available on the Anna Freud website.

It is important to note that young people may be working through their gender identity while dealing with other adversity, ensuring that one considers the whole gamut of Social Graces, including any additional needs or neurodivergence is important in helping them effectively navigate what can be a confusing and very intense time.

Sexual identity

During adolescence young people start to explore their sexual feelings and interests as they begin to form their sexual identity. There are many factors both within the individual and through their interactions with the environment, which influence sexuality development. This includes biological, psychological and social changes as well as political, spiritual, cultural factors.

With the rise in access and use of social media, content in relation to sex and sexuality has never been so readily available, which can be both helpful and harmful during this period of self-discovery. Increased access and exposure to harmful content can negatively influence perceptions and attitudes. Coming soon…..Please click on the link to section on online harms for guidance on keeping young people safe online.]

Young people may become curious or affirm their sexual orientation. There are many ways in which attraction to others is experienced and described, which may change over time. Some of the words used to describe sexuality are available here. Young people may feel confused or uncertain about how they feel, benefitting from opportunities to talk through their feelings with a trusted adult. This may be particularly important for those whose sexual preferences fall outside of societal norm of heterosexuality, who are more likely to experience disadvantage and discrimination as a result of their sexual orientation. This can negatively impact on their mental health. Check out the Young minds website, which has helpful information and advice to support mental health when young people are exploring their sexuality. On their website Young Minds provide useful information and advice for parents and professionals too.

Young people may become sexually active. Fumble provides some handy guides for young people as they begin to experiment sexually. Individualised advice can be sought at the local Sexual Health Clinical which can be found via the NHS website.

It is important to note that young people may be working through their sexual identity while dealing with other adversity, ensuring that one considers the whole gamut of Social Graces, including any additional needs or neurodivergence is important in helping them effectively navigate what can be a confusing and very intense time.

Sexual Identity – Useful Links

Sexual Orientation (LGB+) – The Proud Trust

YoungMinds | Mental Health Charity For Children And Young People | YoungMinds

Fumble’s content series: “Am I trans?” Translating sex, identity & relationships

Find a sexual health clinic – NHS

https://www.stonewall.org.uk/resources/list-lgbtq-terms

https://www.nhs.uk/nhs-services/sexual-health-services/find-a-sexual-health-clinic

Cultural sensitivity and humility – by Power the Fight

At Power The Fight we use the definition developed by Dr Melanie Tervalon & Dr Jann Murray-Garcia:

“Cultural sensitivity/ humility is a lifelong process of self-reflection, self-critique, and commitment to understand and respect different points of view, and engaging humbly, authentically, and from a place of learning. Individuals are encouraged to critically understand their own cultural assumptions, the cultural context in which they hope to operate successfully, and the ways in which institutional structures of power and privilege need to be reimagined to be more inclusive of all ways of being.”

Our 2020 TIP Report found that “[therapeutic services] are significantly impeded by a lack of awareness and knowledge of cultural difference and cultural contexts. This limited understanding and relatability were apparent in both the interactions between therapeutic practitioners and clients, and the structural power dynamics of therapeutic institutions themselves. Culturally disengaged approaches were seen to reduce the success of referrals through poor rates of engagement with therapeutic services and increase the risk of further harm on vulnerable and marginalised groups through misrecognition and misunderstanding.” (Williams et. al 2020)

Since we conducted this research, we have also see the impact that a lack of cultural sensitivity and humility can have on services beyond the therapeutic sector.

Representation Matters:

The TIP Report (2020) found that “For Black people in particular, trusting relationships with professionals relies greatly on representation and cultural sensitivity/humility, with young people and families much more likely to speak with practitioners who share or understand their ethnic background and culture.” (Williams et. al 2020)

Reflecting on the cultural representation within your workforce, or wider sector, is imperative as it can affect whether young people seek help, access support and see your professional role as a career option for their future. However…

Understanding & Trust Also Matter:

The TIP Report also found that practitioners from different backgrounds to those of the young people they are working with can also develop cultural sensitivity. “Trusted practitioners can deliver culturally competent therapeutic interventions. A therapeutic relationship requires trust, which is why young people and families belonging to groups that have been socially marginalised or historically harmed by institutions are unlikely to want to engage with services. This is especially likely if the intervention is seen to be culturally and visibly white and middle class. However, this research has demonstrated that overcoming these barriers is possible. There are many practitioners with unique expertise, shared experiences, or contextual understanding who maintain meaningful and effective therapeutic relationships with marginalised groups.” (Williams et. al 2020)

How can you develop culturally sensitive practice?

Self-reflection & self-critique: The foundation of cultural sensitivity relies on all of us as practitioners understanding and reflecting on our own cultural backgrounds. This includes the biases and assumptions we hold about those from cultures and backgrounds different from our own. Tools such as Social Graces (anchor to social graces section) (John Burnham, Alison Roper-Hall and colleagues,1992) and the Wheel of Power (Sylvia Duckworth) can help us understand on our own cultural identity, while reflecting on bias helps us to challenge any unhelpful beliefs and respond differently in the future. When reflecting on bias, don’t just focus on ‘conscious’ and ‘unconscious bias’, try to take it deeper to think about Anchoring, Bias Blind Spots, Inheritance/Intergenerational Effect, Outcome Bias and the Bandwagon Effect

Understanding and respecting different points of view: Cultural sensitivity encourages us to be curious and non-judgemental about those we work with (both young people, families and our own colleagues). In this way, cultural sensitivity aligns with other key characteristics of our professional practice.

Ongoing learning about the cultural context: No group or culture is a monolith and so it is important that, whether we share that cultural background or not, we keep an open mind and posture of learning about the unique experiences and beliefs of those we work with. Ongoing learning and understanding the reality that we can never know everything about a culture is key to developing cultural sensitivity and humility.

Reimagining institutional structures of power & privilege: Once you have begun reflecting, learning and understanding it is important to take action. Reimagining structures and systems can start small but it does require buy-in and commitment at every level, and a robust plan of how tangible change will be implemented. To plan the action you will take to embed cultural sensitivity you may want to answer the following questions with you team or service:

- What’s going well? In what ways are we already demonstrating cultural sensitivity?

- What small next steps could we take to build on this and become more culturally sensitive?

- What would it look like if we were a truly culturally sensitivity service/organisation?

In this video you can watch Ben Lindsay’s TED Talk on Cultural Sensitivity.

Cultural sensitivity and humility – Useful Links

Resources: TIP Report 2020 Video Summary – https://youtu.be/WbvRmpAMC-o

Ben Lindsay’s TED Talk on Cultural Sensitivity – https://youtu.be/TfIcEYAWqXs

Power the Fight have recently launched an online training platform. You can find out more here https://www.powerthefight.org.uk/what-we-do/training/

Adolescent brain development

Maturation

Over the last two decades, advances in technology and brain imaging have led to significant progress in understanding adolescent brain development.

Although the brain stops growing in size by early adolescence, there are significant structural and functional changes inside of the brain, which helps the brain to become more efficient. This maturation process continues through adolescence and into early adulthood up until the mid to late twenties.

The changes in the brain shape how young people think feel and behave. Understanding adolescent brain development can therefore help to understand young people’s behaviours and the choices that they make.

Structural and functional changes

Whilst the brain does not grow in size during adolescence, grey matter, which contains most of the brains neuronal cell bodies spikes in early adolescence, peaking around 15 years old. Through a process of synaptic pruning this then decreases. Synaptic pruning is the brain’s way of optimising its processing power by eliminating weaker or unused connections between neurons and strengthening the ones that are used more often- think use it or lose it! You can imagine how much quicker and easier it is to take a well-trodden path over an overgrown one. In the same way the brain needs to find ways to be efficient amongst a myriad of possible pathways.

At the same time that grey matter is decreasing, white matter volume increases. White matter is made of myelinated axons, which connects different parts of the brain. This allows for faster communication between brain regions, enhancing the communication network.

Reward system sensitivity

There is some evidence to suggest that during adolescence there is increased activity in the limbic system – which is often referred to as the “emotional brain”. This part of the brain plays a crucial role in regulating emotions, memories, motivation and behaviours that are essential for survival. As well as promoting survival through “fight or flight mechanisms, this region is also involved in pleasure and reward. Adolescent brains become particularly sensitive to rewards, amplifying the pleasurable feelings that come alongside reward- be it through food, social rewards or sensation and/or risk seeking behaviours.

Whilst this part of the brain is at its most sensitive, the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for planning, organisation and impulse control remains under development. This coordination centre is the last area to mature, which helps to understand why young people are more likely to engage in impulsive, risky and sensation seeking behaviours and why they are particularly vulnerable during this stage. This includes a vulnerability to exploitation, where the physical, psychological and social rewards provided through the process of exploitation are likely to be particularly intense and pleasurable for young people.

Taken together, the sensitivities in the “emotional brain”, combined with the underdeveloped organisation centres explains why very often young people will feel before they think. It is, therefore, helpful to support young people’s emotion literacy and regulation strategies- see Working with emotions section [insert link].

If you’re interested in finding out more, there is a great TED talk by Sarah Jayne Blackmore, Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience.

Individual difference

No two brains are the same.

Brain changes and development can happen to differing extents and at different rates depending on a number of factors, including neurological differences and/or environmental factors such as exposure to adverse or traumatic experiences. As noted by Coleman, (RIP, 2020) there is evidence to suggest that growing up in restrictive or deprived environments can contribute to delays in brain development.

Brain imaging studies indicate that trauma can impact on the development of several parts of the brain including the threat processing and emotion regulation systems as well as executive functions and memory. The threat processing system can be become overactive, meaning that the fight or flight response is easily activated resulting in hypervigilance. Development of the prefrontal context (the part of the brain responsible for planning, organisation and impulse control) may be delayed or underdeveloped impacting on decision making, impulsivity and its ability to regulate the threat processing system. Ultimately, the brains’ ability to calm itself when (easily activated) is disrupted. See further information in Working in Trauma Informed way section [to link]. Traumatic experiences can also contribute to high cortisol levels (stress hormone), which can impact on memory processing. This can lead to problems with learning, memory recall and difficulties in distinguishing between past and present danger resulting in flashbacks.

But the good news is, that there is evidence to suggest that even when exposed to adverse or traumatic experiences, the brain has a remarkable ability to adapt and recover. Therefore, creating safe, nurturing environments and providing appropriate support can be transformative in helping overcome challenges to support young people to flourish. In any event, supportive structures, encouragement and positive encounters and activities will help to shape the neural and behavioural pathways that forge during this formative, transitional and potentially transformative period.

For young people with Acquired Brain Injuries (ABI) there may be additional challenges. Whether they acquired their brain injury as a young child, or later on in adolescence, function around memory and consequences can develop very differently for some of these young people. This can also lead them to be more vulnerable to exploitation, as they may have a very different understanding of risk and reward than their peers. The charity Cerebra has a lot of resources and helpful factsheets for parents, carers and staff on dealing with various aspects of behaviour and emotions for children with an intellectual disability that may be the result of a brain injury.

Foetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder (FASD) may be present when a child has been exposed to alcohol consumption in utero. Parents and carers report that it can be common in children who have been adopted or who are in care, but it may occur in any of the population, with some estimates putting it at around 5% of the population. Children who experience this condition may struggle among other things with impulse control, processing actions and consequences, social skills and may be particularly sensitive to criticism and raised voices. There are varying accounts across the world of how FASD correlates with involvement with the Justice system, but some findings suggest that there is a heightened risk if someone has the condition without support in childhood and adolescence.

It is important to know it may be difficult to diagnose FASD unless there is a definitive account of maternal alcoholic consumption while pregnant, but within the useful links section you can find resources on helpful ways of working with children and young people who may or are suspected to have this condition. There are also significant overlaps in presentation with other forms of Neurodivergence, and being professionally curious about what might be driving different difficulties for children is important when considering how to intervene.

Individual Difference – Useful Links

A Call for Greater Attention to Culture in the Study of Brain and Development – PMC

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9356540/#R121

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9356540/#R3

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9356540/#R94

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9356540/#R121

Acquired Brain Injuries (ABI)

https://cerebra.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Managing-challenging-behaviour-jul21.pdf

Foetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder (FASD)

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder

https://www.fasdnetwork.org/resources.html

https://www.adoptionuk.org/fasd-hub-england-factsheets

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160252717301073?via%3Dihub

Cultural influences on brain development

Little attention has been paid to cultural and ethnic variation to understand how cultural influences impact on brain development. For example, there is less evidence of heightened parent-child conflict, mood disruptions, and risk-taking behaviour, in non-Western cultures than Western cultures (Arnett, 1999; Mead, 1928; Schlegel & Barry, 1991).

It is not clear whether there are neurological implications or explanations for this, for example whether cultural stereotypes of adolescence impact on brain development through self-fulfilling prophecies via neural processing (Qu, Jorgensen, Telzer, 2020). There is increasing interest in this area. We will continue to update our pages with new and relevant information.

Cultural influences on brain development – Useful Links

Appreciating neurodiversity, and considering children with Autism, ADHD and other additional needs or disabilities in your work

Experiencing the world differently

There is variation in how every brain develops and this is why every individual experiences the world in their own unique way. Young people who are neurodivergent may experience and react to the world differently, in a way that is not “typical” of the dominant societal architype.

Adolescence is considered to be a critical period for young people who are neurodivergent as additional divergence from neurotypical development appears. This can include differences in cognition, attention, mood, learning and social interaction. Consequently, navigating the many changes that occur through adolescence can be particularly challenging for young people who are neurodivergent. As they become more independent and expectations from others grow, there may be increased demand on cognitive tasks such as planning, organising, adapting and regulating, which may be the very cognitive skills compromised by an individual’s particular neurodivergence.

Furthermore, the orientation towards peers and the skills required to establish and maintain reciprocal relationships can be particularly confusing. Social skills training can be beneficial for any young person and may be particularly helpful for young people who struggle with social processing and interactions.

Young people who are neurodivergent are likely to experience the ‘double empathy problem’. This is where they may struggle to identify and relate to the experiences of others, but others also struggle to empathise with the perspective of the neurodivergent young person. This is due to a breakdown in reciprocal communication, caused by contrasting experiences of the world. Therefore, those who are neurodivergent are particularly vulnerable to social isolation, being misunderstood and expected to exert additional effort to empathise through a neurotypical lens.

That said, it is important to remember that neurodivergence relates to variations rather than deficits in how different brains process, respond, interpret and experience the world. There are many strengths and skills that exist alongside the challenges and difficulties of being neurodivergent. Embracing an individual’s strengths and accommodating differences will enable and support neurodivergent young people to thrive.

For some young people who are Neurodivergent, their experiences and needs may reach a point where they are clinically significant. They may for instance be diagnosed with Autism, ADHD or another specific Neurodivergence. Only appropriately qualified health professionals, such as paediatricians, psychiatrists or specialist clinicians, can make formal diagnoses of Autism or ADHD. However, support should be based on a child’s individual presentation and needs, not dependent on a formal diagnosis.

This page, from the National Autistic Society explains more about the Neurodiversity movement, and Neurodivergence, and some of the specific expressions in Neurodiversity – for some advocates of Neurodiversity, the list is very broad – for some it is much more specific, we talk about it in these pages as a way of being as inclusive as we can to young people who see the world differently, whether or not a young person is diagnosed with a specific Neurodivergence.

It is vitally important that you consider a young person’s individual communication needs when considering any Neurodivergence, and to note that communication and social cues may look different to a child who is ‘Neurotypical’, but also different to other children who might be diagnosed with a similar Neurodivergence.

Here are some quick tips for considering how one might need to structure a direct work session for a young person who is Neurodivergent, this is not a definitive list, and note the invitation to ‘consider’ rather than ‘do’, as noted above all young people are different, and it shouldn’t be assumed that what works for one child with a particular sort of Neurodivergence works for all – please see the resources at the end of this section for more detail:

- As already mentioned, use the expertise of a young person’s parents, carers and professionals (if safe to do so) who already know them to ascertain how best to communicate. Ensure on first contact with them you are clear on who you are and why you are there.

- Relational Practice, as discussed elsewhere in SAIL, is perfectly possible with young people who are Neurodivergent; what it looks like to build empathy and rapport may just be slightly different.

- Consider whether making efforts to sustain eye contact is helpful, some young people who are Neurodivergent, and specifically young people with Autism might find this very uncomfortable

- Think about your environment. Consider whether a young person might need an activity to keep their hands or body busy, or be negatively responding to sensory stimuli such as smell or sound.

- Consider when you have your sessions. Sometimes seeing a young person earlier or later in the day can mean they are better able to concentrate on what you are saying.

- Consider whether the use of metaphors and similes in direct work will be helpful for them. Sometimes speaking plainly and directly is preferred.

- Young people may ‘stim’ during conversations, which are often characteristed by involuntary movements or noises – these are usually nothing to be concerned about; Claire’s talking head below talks about this.

- Some young people may stim with more extreme behaviour such as hitting themselves, or banging their head on a table or wall. This article gives some tips of how to manage self-injurious stimming:

- Particularly when getting to know a young person, consider whether comments you perceive as ‘rude’ or ‘disrespectful’ might simply be a different way of communicating. As you build a relationship with a young person, you may get a better understanding of what they mean when they phrase things in certain ways, and what will be helpful for them in terms of how you respond.

Below are some videos from London’s Parent Carer Forum talking about some tips from their experience of structuring a session with a neurodivergent young person:

Experiencing the world differently – Useful Links

Specific neurodivergence

Please note that this section is subject to ongoing input from experts by experience and by specialism, and the content will continue to evolve.

Below are some guides to specific types of Neurodivergence that are more common, and may be helpful to your practice:

Autism:

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/resources-for-autistic-teenagers

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD):

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/adhd-children-teenagers

Demand Avoidance:

We have been asked to mention ‘demand avoidance’, sometimes called ‘Pathological Demand Avoidance’ or PDA by some experts by subject and experience, as a form of Neurodivergence that at the time of writing is being experienced and described more by parents and professionals. This article explains a bit about what it is, what might be helpful for professionals, parents and carers, and where it currently fits in wider Neurodiversity:

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/demand-avoidance

PDA Society – Pathological Demand Avoidance

Specific neurodivergence – Useful Links

Autism

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/resources-for-autistic-teenagers

ADHD

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/adhd-children-teenagers

Demand Avoidance:

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/demand-avoidance

Neurodiversity, safeguarding and exploitation

The link between Neurodiversity, safeguarding and exploitation is complex. Under Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE), adults must remember that while neurodivergence can affect communication and behaviour, this must never prevent us from recognising or acting on possible safeguarding concerns.

Neurodivergent children may find it harder to disclose harm or be heard; professionals working with children must therefore take extra care to ensure their voices are understood and that professional curiosity is maintained.

Part of working with a young person who may be at risk in these areas might be considering with the professional network how Neurodivergences such as ADHD or Autism might affect how they see the dangers other adults see around them and what specialist help across health, education and social care might be necessary to help them thrive. This is best done alongside them, as well as with the parents, carers and professionals who know them well.

Neurodiversity, safeguarding and exploitation – Useful Links

Other additional needs and Special Educational Needs & Disability (SEND)

Please note that this section is subject to ongoing input from experts by experience and by specialism, and the content will continue to evolve.

There is a huge amount that can be written about various different physical and learning needs young people may have which might affect their sessions with you. At the most basic physical level, a condition like Sickle Cell Anaemia or Diabetes may significantly affect mood and energy at school, particularly if it is a condition they struggle to manage. Even a mild learning or communication difficulty may prove a source of intense frustration as a young person struggles either to understand the behaviour of their peers, or communicate their views, or both. If you are aware a young person has a condition, or a disability, the best thing you can do as a professional is research it, and respectfully ask the young person and those who know them how it affects them if at all (it may not).

It is vitally important to ensure you work with professional curiosity to understand what this condition means for them, rather than working to preconceived notions and stereotypes, while also acknowledging that for some young people it is a fairly incidental part of their life, and for others it forms a significant part of their identity.

You may also be interested in exploring other related SAIL topics such as: Professional Curiosity.

Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN) and criminal justice – hidden difficulties and opportunities to support

Difficulty in clearly communicating what is happening for you, and articulating it in ways that others understand is a significant risk factor in safeguarding. When a child has difficulty expressing themselves, it leaves them more open to being abused and exploited. It also means that they might use behaviour to communicate if they feel they are unable to make their fears or frustrations known verbally. While this is more known and accepted for children who are – for instance – non-verbal, for children where there is a less obvious communication need, some of their support requirements may be hidden

In education, most of the curriculum is taught through language (both spoken and written), meaning that accessing and succeeding in education is often difficult for those with Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN). It makes sense then, that SLCN are, as well as Autism, one of the most common reasons children are supported and referred for Education, Health and Care Plans in London.

Some surveys found around 70% of children known to youth justice services have Speech, Language, Communication Needs (SLCN).

It should be no surprise then that in the youth justice population, it is estimated that a significant proportion of children have SLCN. Some surveys found around 70% of children known to youth justice services have SLCN. Depending on the survey and the setting, it has sometimes been a higher percentage. However, unfortunately, it is rare (research found only 5% of children) that these needs are identified prior to children coming in contact with the justice system.

This poses a useful challenge for professionals in how they communicate with children known to Youth Justice Services, but also whether more effective identification and support earlier on in their journeys might divert children away from this pathway. Considering how to support these young people may be a vital part of helping them towards safety.

Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN) and criminal justice – hidden difficulties and opportunities to support – Useful Links

Transitions into adulthood for children with Neurodivergence, Additional Needs and Disabilities and potential cliff edges of support

Please note that this section is subject to ongoing input from experts by experience and by specialism, and the content will continue to evolve.

A common experience for young people, and parents and carers with additional needs is a significant mismatch between support given pre and post 18. Adults Social Care thresholds are sometimes very different to Children’s Services thresholds, and young people who receive a service under 18 may not qualify for any support post-18, or only qualify for support that is much more limited.

Services also legally shift from being proactive and assertive in managing safeguarding risk, to services which consider safeguarding, but have to do this work much more consensually with young adults unless they legally do not have capacity to make decisions through significant disability or mental illness; the amount of young adults this applies to is small.

This presents a safeguarding challenge for young people who may have significant input and services keeping them safe until their 18th birthday, when they may then face a cliff-edge of support. Good practice guidance suggests that children who may transition to adults’ services should have transitions work starting between the ages of 14-16 – resource issues often make this challenging to implement.

As a practitioner, one of the questions that is important to ask if you are dealing with a young person who has additional needs at 15 or 16 is what the plan of support will be post-18. This may require research and advocacy with adults’ health and council services (whether statutory or not) early to ensure the relevant assessments are undertaken and referrals made. It may also be about ensuring the young person is being prepared on how to self-advocate, or access advocacy and access the right services themselves, or that their family is empowered to support them.

There are however models of good practice developing in London considering ways to more effectively support young people into young adulthood, and services that are increasingly also bridging this gap, these are explored in the Transitional Safeguarding section linked below.

Leaders and managers should consider what they can do to bridge gaps and build understanding between services.

You may also be interested in exploring other related SAIL topics such as: Transitional Safeguarding

Working with emotions

Emotions experienced by young people

The significant biological, psychological and social changes that occur during adolescence can help to explain the intense and fluctuating emotions experienced by young people during this time in their development, which can also be closely felt and impact on those around them.

The changes that are happening (both noticeable and unnoticeable) to a young person’s body and social contexts can be a time of mixed emotions and a source of stress. The brain changes [link to neuro section] that are happening mean that the “emotional brain” is more easily activated, whilst the control centre of the brain (the prefrontal cortex), which is responsible for planning, organising and managing impulses remains under construction and is the last part of the brain to develop. This means that young people are likely to feel emotions strongly, without support from the prefrontal cortex to control how they respond and react to these emotions. This can be compounded for young people who have been exposed to adverse and/or traumatic experiences, who consequently have easily activated fight or flight responses.

Working with emotions, both that of young people and their networks including professionals has been commonly referenced as an important area for Adolescent Safeguarding. In preparation for this resource, practitioners, managers, leaders and policymakers noted that working with emotions was important to them. Within this section, we consider the importance of emotional awareness, literacy and regulation and provide some practical tools taken from the Your Choice programme. We will also consider the importance of acknowledging and responding to our own emotional responses- as individuals and systems, triggered by our work with adolescents.

What do we mean by emotions?

Emotion is a commonly used term, but hard to define given its abstract nature.

In SAIL we refer to Emotions as an internal state, that is an automatic, unconscious physiological reaction to an external or internal event or situation. Often the term emotion is used interchangeably with the word “feeling” and we will do so in SAIL. However, by way of introduction to the topic it is helpful to understand the distinction between the two terms. Whilst emotions are considered to be those automatic unconscious reactions to things happening around us, feelings on the other hand relate to the conscious awareness and the way that we describe those emotional responses. That is, how we make personal sense of our emotions, which will be influenced by many factors including previous experiences, cultural backgrounds and current circumstance. During their early development a child will often look to the adults around them to make sense of the bodily responses they experience triggered by an event. For example, during a thunderstorm a child might be startled by the sound of thunder (the event), which causes their heart to beat faster (emotion). If someone around them reacts to their bodily response by hiding behind a pillow, stating that they feel scared (feeling) then the child begins to make associations between what is happening in their bodies (emotion) and how they describe this to themselves and other (feelings).

Emotions are a normal part of what it is to be human and can range from pleasurable to painful experience. Each of us will experience emotions in our own way- we all have them. Finding ways to help young people and their networks to name, understand and respond to their own emotional experiences will support their psychological health during adolescence and beyond. Being able to understand and respond to our own emotional experiences triggered through our work, often dealing with big emotions, is important for our own wellbeing but also provides an opportunity for learning and modelling through co-regulation.

What good are our emotions?

Emotions give us information, communicate to and influence others and motivate and prepare us for action. They provide a signal that something in our environment is happening.

Our emotions often show in our facial expressions, body language and tone of voice. This helps to communicate to others how we are feeling, which may impact how they respond to us. For example, if we are feeling sad, then this may be evident in a downturned mouth, lowered eyelids, a drooping lower lip and you may notice tears in the eyes or rolling down the face. This may prompt others to comfort you.

Emotions also motivate and prepare us for actions. For example, if you are presented by a threat in your environment (either internally or externally) then your bodily responses will likely prepare you to respond by raising your heart rate- sending blood pumping to your muscles in order to fight or flea from the threat. In addition to the well-known “fight or flight” responses, the freeze and fawn responses are also common in the face of a perceived threat. This means that an individual may freeze and become immobile in order to avoid fight and potential harm. Alternatively befriending, appeasing or helping the threat may avoid conflict and harm. This is referred to as the fawn response, which can help to understand how exploitative relationships develop and are maintained.

The fight, flight, freeze or fawn responses are grounded in Darwin’s evolutionary theory, which suggests that these responses have been key to survival of the human species. By helping young people to understand the adaptive function of emotions, it can help them understand in a non-judgemental way, how and why they respond in certain situations.

However, Darwin’s theory may not be culturally relevant for some young people and their families. There is no one size fits all to help someone understand their inner experiences and it is important to consider context and culturally relevant and responsive approaches taking into account interests, beliefs, neurodiversity and communication styles, which may be similar or different to your own.

The importance of individual difference

It important to acknowledge that identification and interpretations of facial expressions are not universal and may be impacted by individual difference including cultural norms, exposure to adverse and traumatic experience and/ or neurodivergence. Therefore, it may be helpful to find ways to support young people to recognise emotions (in themselves and others). Using pictures cards with labelled facial expressions or playing a game of Guess Who- using facial expressions to identify characters in the game can provide interactive ways to identify and talk about how different emotions can present in ourselves and others.

Young people who have been exposed to trauma, particularly interpersonal trauma such as abuse, neglect or exposure to violence are more likely to experience a hostile attribution bias. That is, a tendency to interpret the actions of others as hostile. For example, if someone bumps into them, they will assume that this was done deliberately with an intention to cause harm. This hostile interpretation means that the “fight or flight” responses are more easily activated, with a reactive, aggressive response more likely.

Young people who are Neurodivergent may also misread other social cues, or perceive changes to routine as threatening in ways that may be unclear to adults or young people who are Neurotypical. It is important if you know or suspect that a young person is neurodivergent that you try and work out with them and their network what some of the trigger points for anxiety or hostility might be so that you can work around these, either by removing triggers, or helping them navigate, manage and understand discomfort that may be unavoidable.

Helping young people to understand how earlier experiences may have impacted on how they understand and respond to their environment can help them to recognise and intercept patterns of behaviour. That said, the context of young people’s live, particularly those within Adolescent Safeguarding services, may well find themselves in hostile and dangerous situations and so their interpretations of situations may indeed be accurate and necessary to keep themselves safe. Therefore, supporting young people to identify indicators of safe and unsafe situations is an important aspect of your work.

Emotions in ourselves

Working with big and fluctuating emotions in others can trigger our own emotional responses and reactions. Furthermore, exposure to other people’s trauma, increases the risk of negative effects of vicarious trauma. Therefore, in order to help others it is so important to pay attention to and invest in our emotional wellbeing. In doing so, this can enable you to co-regulate with the young person if they are dysregulated, providing valuable opportunities to model appropriate emotional awareness and regulation skills. In Your Choice, coaches are encouraged to regularly rehearse the tools and techniques for themselves- not only to support them in their practice but to help them to prioritise their own wellbeing too.

Access to reflective supervision, which allows you to consider not only what you may be bringing to your work but also the impact on yourself is a necessary and important practice priority. It can be challenging to prioritise reflective spaces amongst the demanding and busy workloads often dominated and impacted by crises. However, ensuring that there is dedicated space to reflect and invest in ourselves and each other can bring greater perspective and effectiveness, motivation and sustainability in our work to support young people, families and communities in need.

Understanding and regulating emotions

Working with adolescents and with families that may have a history of traumatic experience(s) means that you are likely to be dealing with big and fluctuating emotions. Finding ways to help young people (and their networks) understand their emotions and feelings [link back to earlier section what do we mean by emotions] can help them to respond to them in a way that is helpful and not harmful.

Emotion regulation refers specifically to the skills that we can use to reduce the intensity of emotions so that the “rational part of the brain” can engage and enable healthy and safe responses that are aligned with an individual’s values and aspirations.

The first step in effectively managing emotions is learning to recognize and name them. In the Your Choice Programme, practitioners are encouraged to work with young people and their networks to find creative ways to help young people to recognise their inner experiences, their bodily responses and name their feelings using their interests to engage them in meaningful exploration. Noticing what is happening in their bodies may be particularly challenging for young people who are neurodivergent. Some young people may not be aware or indicate that they are feeling overwhelmed and can become skilled at masking their inner turmoil (particularly those with Autism) until such a time that they are in a more familiar environment, prolonging a meltdown or shutdown.

Therefore, it is important to find creative ways of helping them to understand what is happening in their bodies.

Below are some tried and tested techniques that you may wish to

Name it to tame it

The name it to tame it technique is a great example of a simple but effective technique, noticing what is happening internally can help to create a distance and reduce the intensity of an emotion. This requires young people to be able to express how they are feeling. Plutchik’s wheel of emotion provides a useful resource describing a range of different feelings. It also shows how different emotions relate to each other and the varying intensities in which emotions can be felt. For example, ranging from apprehension to fear to terror.

The wheel of emotion (Plutchik Wheel of Emotions, 1980) provides a visual aid, which could be gamified or used to prompt conversation to help to develop emotional literacy and awareness.

Here are some suggested prompts you might want to include;

- which of the feelings do you feel the most?

- which feeling do you prefer?

- which feeling don’t you like?

- what do you notice in your body when you are feeling (name a feeling)?

- how would I know if you are feeling (name a feeling)?

- what are you doing when you are feeling (name a feeling)?

- which feeling do you find difficult to manage?

- what helps when you are feeling that way?

As young people become better able to name the emotion, encourage them to start to name emotions (in their head or out loud) as they notice them. When you are together say what you see to help them to recognise the emotion and validate the emotion. For example, “I can see that you’re upset. I can understand why losing your phone would upset you”. Validating emotions can be a helpful response in itself. Even if you may not agree with or understand how someone (including yourself) is feeling, acknowledging the emotion can help to reduce its intensity so that they can start to regulate and respond in a safe way.

Techniques taken from Your Choice

Your Choice is a pan-London programme using CBT to empower young people to work towards their goals and aspirations to support their safety and wellbeing.

Understanding and responding to emotions is often referred to as emotion regulation. Trying out and practicing different emotion regulation techniques is an important life skill and can be particularly helpful for young people given their developmental stage- with the malleability of neurological and behavioural pathways and the intensity in which they are likely to experience emotions during this period.

In Your Choice, practitioners are encouraged to work with young people and their networks to find creative ways to help young people to recognise their inner experiences, their bodily responses and strategies that help when they are feeling overwhelmed by an emotion, drawing on a young person’s interests to engage them in meaningful exploration. For example, a young person who enjoys football, would be encouraged to consider how they would be feeling during a penalty knockout, what they would notice in their bodies to help them understand and respond to the feeling. They might also find it helpful to try out some football drills that offer intensive exercise, which is a simple and effective emotion regulation technique.

Grounding techniques can help to take the focus away from our internal worlds including thoughts, memories and images. Here are some techniques from the Your Choice programme that you might like to try.

- Take 5

Take 5 is a quick technique that can be used anywhere as it simply requires you to name 5 things that you notice for each of your senses.

There is no one technique that is superior in regulating emotions – what works well will be a very personal thing. Young people should be supported to try out a range of techniques, adapted in a way that makes most sense for them. Once they have found something that feels helpful for them it is important to practice these techniques as often as they can. This will not only support their overall wellbeing but will also mean that they are accessible to them when they need them most.

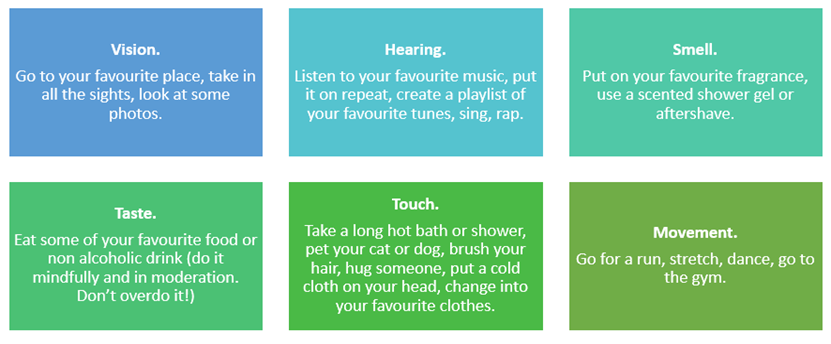

2. Six Sense Self Sooth

This exercise helps to find ways to comfort and nurture oneself in a healthy and safe way.

3. TIPP

When emotions are overwhelming, and you are not processing information, it can be helpful to TIPP the body chemistry.

- T Temperature. Splash your face with cold water or place a cold pack on your eyes or cheeks. Hold for 30 seconds.

- I Intense exercise. This can help to calm the body down when it is revved up. Do some intense aerobic exercise, even if for 10-15 minutes. This will help to burn off the physical energy. You could try running, fast walking, jumping jacks, dancing weightlifting. Be careful not to overdo it though.

- P Paced breathing. Slow down your breathing. Use the hand method. Breathe deeply from the tummy, breathe out more slowly than you breathe in. Do this for 1-2 minutes.

- P Progressive muscle relaxation. Tense and relax each muscle group in turn (see progressive muscle script).

Great news! Your Choice is currently being accredited. If you’re interested in delivering Your Choice in your area please reach out to our Your Choice team .

Understanding and regulating emotions – Useful Links

Understanding young people and their mental health – in development

This topic within SAIL is still in development with colleagues and partners and will be coming soon!

If you’d like to directly contribute to this section then we’d love to hear from you – whether it be providing written content, sharing research, resources being part of the ‘Talking Head Series’ – you can read more about the ‘SAIL talking head’ series here!

Working creatively with young people

Maximising your own creative skills to engage safely

Engaging young people meaningfully requires you to draw on what you know and understand about adolescent development and what that means for each young person. It requires you to find ways to get to know each young person uniquely, to explore, ignite and nurture what drives them, their interests and their aspirations- building on their sense of self and autonomy.

Working with adolescents provides a great opportunity to utilize and maximize your own creative skills to ensure that you can engage and work with young people safely in a way that feels accessible, inviting and responsive to their unique needs and aspirations.

The biological, psychological and social changes that occur during adolescence requires thoughtful consideration for where, when and how you approach your work with young people – to work with their unique rhythms in order to maximize opportunities for reachable, teachable moments. Adopting a flexible approach may take you outside of your own comfort zone in order to meet the young person where they are at both physically (where appropriate and safe) and psychologically, including considering relevant factors around Neurodiversity, both for the young person, but also perhaps yourself. Balancing the needs of the young person versus your own professional capacities and capabilities is an important consideration to reflect on during supervision.

The Your Choice programme emphasizes the importance of working creatively to engage, motivate and support young people to engage in positive, pro social behaviours, aligned with their values, interests and aspirations.

Hear from Nana Bonsu, Director of Relational Practice in her video prepared for SAIL where she promotes the importance of creativity and new ideas in your practice.

Building on the existing therapeutic resources in multi-disciplinary adolescent services

.

Your Choice is a cost-effective framework developed for London’s practitioners supporting children affected by extra-familial violence and related harms.

It brings the principles of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to current best practice in violence-reduction and related partnership approaches. Your Choice fills a practice gap by moving beyond understanding why a child may behave in a certain way to providing tools and techniques to support their psychological health

What is the programme?