PATHWAYS: Safeguarding adolescents in the London context

“Care as a verb not a noun: care is something we do for children, not a place we put them” – Dez Holmes, Director of Research in Practice

Navigate SAIL

Topics in this Section

Designing services to keep young people safe

In the first of our examples Sara Rahman describes the approach which is being taken in Lewisham where, as a Families First for Children pathfinder, the children’s services partnership has designed and implemented a Multi-Agency Adolescent Protection Team at the heart of its reformed services.

London continuum of need

Sound decisions in safeguarding rely on practitioners’ ability to synthesise information from a range of sources, critically evaluate the level and nature of risk, and remain alert to missing, conflicting, or ambiguous evidence.

High-quality safeguarding depends on high-quality decision-making. This is particularly true when working with adolescents, whose experiences often span multiple environments and whose vulnerabilities may be complex, dynamic, and less immediately visible.

A shared understanding of thresholds of need is crucial for ensuring consistent and appropriate responses across all services. In London, the key reference point for this is the London Continuum of Need Matrix. Although not a statutory instrument, it has been endorsed by all of London’s Local Safeguarding Children Partnerships as a shared reference point for practitioners. The Matrix provides a common language and framework for identifying risk and vulnerability, encompassing both familial and extra-familial harm.

Its purpose is to support consistent and proportionate responses to concerns by outlining four levels of need and offering illustrative indicators for each. These levels range from universal support to acute or specialist intervention, helping professionals to make informed judgments about when and how to escalate concerns.

The document sets out a clear framework for understanding different levels of need and the appropriate service responses. It emphasises the importance of early help, outlines the graduated approach to intervention, and promotes a common language for assessing and discussing concerns. The aim is to support informed and proportionate decision-making, ensuring that children and young people receive the right support at the right time.

It stresses that all practitioners need to be alert to bias and inequality that can affect decision making and to reflect on assumptions related to identity, background and behaviour.

- Adultification – seeing children as more mature and less vulnerable than they are

- Diffusion of responsibility – waiting for someone else to act

- Source bias – judging information by who says it, not what it is

- Confirmation bias – focusing on information that supports what you already believe

- Risk aversion – avoiding uncertain options even when they may be better

While all sections of the matrix are relevant to young people, there are specific sections which have particular relevance to working with adolescents. Notably, these include:

- Education

- Sexual Abuse or Activity

- Police Attention

- Extra Familial Harm

This document should be used alongside the London Safeguarding Children Procedures to support thoughtful, and safe decision-making.

Safeguarding Adolescents in the MASH

In practical terms, the London Continuum of Need Matrix should be an essential point of reference from the outset, particularly in the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH).

This is especially important when working with adolescents, whose experiences often span multiple contexts and whose vulnerabilities may be harder to interpret.

Practitioners in the MASH should avoid applying thresholds solely on the basis of the referral content and instead remain alert to the full range of possible, sometimes overlapping, harms whether from family relationships, peer associations, exploitation, online activity, or community dynamics. It is vital that practitioners in the MASH can see beyond a binary distinction between harm within the home and harm outside it.

Continuum of Need – Useful Links

ROTH (Risk Outside the Home) pathways

ROTH (Risk Outside the Home Pathways) were introduced by Professor Carlene Firmin in recognition of the fact that traditional child protection processes were rooted in assessing and intervening where intrafamilial abuse or neglect was occurring and where such harm was attributable to the (in)action of parents or carers.

These processes were often perceived as blaming and disproportionately focused on parental deficiencies and failure to ‘control’ their children and keep them safe.

The ROTH Pathway, as defined by Professor Carlene Firmin and embedded within the contextual safeguarding framework, recognises the importance of parents as partners and that significant harm to children and young people can occur in contexts beyond the family such as peer groups, schools, neighbourhoods, and online spaces.

The focus of a ROTH pathway is on the collective capacity of a partnership to safeguard young people at risk of significant harm, rather than solely their parents, As such is ensures a child protection level responses to children and young people who historically could have been screened out of child protection processes, not because they were not at risk of significant harm, but because that harm was not attributable to their parents or carers. It loses none of the oversight and rigour of child protection plans but does this using a contextual lens to assess and intervene where traditional child protection methods may not be sufficient or appropriate.

ROTH Pathways were designed to complement existing child protection pathways but:

- Focus on where a young person is safest and least safe – weighting the influence of different contexts to develop a plan for to build safety around young people.

- Recognise parents as potential protective partners in the child protection process, rather than the subject of the process.

- Adopt contextual safeguarding principles, to explore young people’s needs, access to safe adults and environmental drivers of harm in the contexts where young people are unsafe, and build the collective capacity of a partnership to respond accordingly.

- Use different tools and frameworks, such as context assessment and planning tools, safety mapping and peer assessment activities with young people, community-facing family group conferences, and other welfare-orientated interventions that move beyond ‘disruption’ and ‘dispersal’ as mechanisms for responding to extra-familial contexts.

In efforts to avoid the punitive feel of traditional Child Protection Plans, some local authorities have chosen to hold these cases at Child in Need level. However, this is not acceptable where the threshold for significant harm is met. Holding young people at children at Child in Need status in order to avoid statutory child protection processes undermines the seriousness of the risk and the legal safeguarding responsibilities involved. ROTH pathways provide a middle-ground – by removing the sometimes punitive and/or parent-focused feel of a child protection process, while also creating space for collaboration with parents/carers and young people to build safety for those who have reached a threshold of significant harm.

That said, some local authorities have found value in the ethos and methods of contextual safeguarding, and have embedded those approaches into Child in Need plans in cases where the harm is concerning but does not meet the threshold for significant harm. This is an appropriate and creative use of the framework – provided that the level of risk and legal duties are properly recognised.

In summary:

- If significant harm is suspected – whether within or outside the home – Section 47 enquires must be initiated.

- The ROTH pathway can enhance, but does not replace, statutory safeguarding processes.

- Contextual safeguarding approaches can be usefully incorporated into Child in Need planning - but not used to avoid child protection duties where they apply.

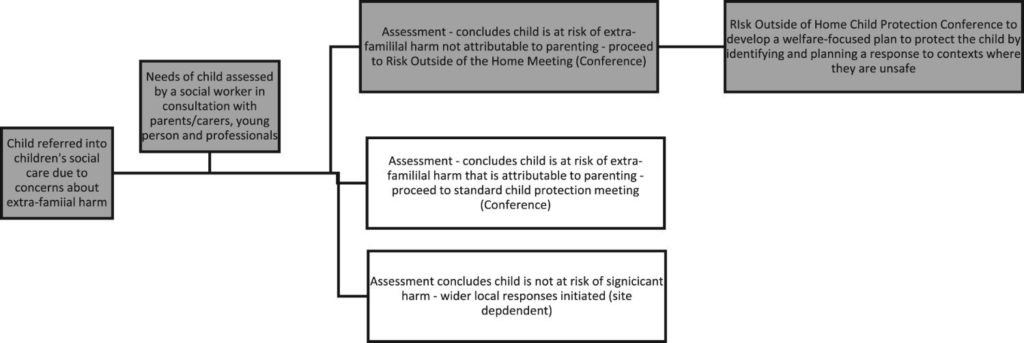

The following diagram taken from Binaries and Blurred Lines: The Ethical Stress of Child Protection Social Work in the Grey of Extra-Familial Harm (cite properly) illustrates the pathway.

Stages to risk outside of the home child protection pathway (in grey).

A ROTH pathway should sit alongside, not outside of, traditional child protection. The pathway is underpinned by s.47 and utilises the same activities such as strategy discussions, enquiries, conferences and reviews. Professionals involved in ROTH pathways may still connect into wider pathways within social care and the wider safeguarding partnership including:

- Panels and multi-agency structures that coordinate safeguarding responses to groups and locations.

- Screening and assessment tools tailored to extra-familial risk (e.g. exploitation risk assessments, peer assessments, safety planning in public spaces).

Contextual safeguarding – co-produced with Professor Carlene Firmin, Professor of Social Work at Durham University

Contextual Safeguarding is term introduced by Professor Carlene Firmin in 2015 to describe her vision of a safeguarding system that would be able to assess and intervene to create safety in the extra-familial contexts where young people often experience harm.

While adolescent safeguarding refers to the broad system of protecting young people from harm, contextual safeguarding is a specific approach within that system that emphasises the importance of understanding and responding to the social, school, peer, and community contexts in which harm occurs.

This focus makes it ideally suited to the complexities of adolescent risk, and it is widely recognised as a progressive way forward in safeguarding practice. However, as Professor Firmin notes, Contextual Safeguarding remains an evolving approach and is designed to offer a set of principles upon which practices/policies can be built rather than provide an established ‘model’.

As initially developed by Professor Firmin and her colleagues at Bedfordshire, and further implemented and enhanced at Durham University, Contextual Safeguarding:

- recognises relationships young people form in peer groups, neighbourhoods, communities, schools and online can feature harm, abuse and violence

- recognises that parents sometimes have little influence over these contexts, and young people’s experiences of extra-familial abuse can undermine child-parent and family relationships, and

- expands the objectives of child protection systems in recognition that young people are vulnerable to abuse in a range of different social contexts

The approach is organised into four system ‘domains’ or ‘objectives’, and underpinned by six values:

- Collaborative practice with young people, families, and communities—not as passive recipients of services, but as active partners in building safety

- A rights-based lens, upholding both children’s and broader human rights in the safeguarding process

- Strengths-based thinking, which seeks not only to mitigate risk but to build on existing protective factors and capabilities within individuals and their environments

- Grounding in lived realities, which means understanding safety and vulnerability from the perspective of the young person—not just through professional interpretation

- An ecological model, which views harm as shaped by layers of context—individual, group, place, system—and encourages intervention across those levels. It also recognises the influence of broader structural factors such as inequality, discrimination, and marginalisation.

- Caring: which means responding to extra-familial harm through relationships between young people, their parents/carers, wider communities, and with and between the professionals who support them, that are characterised by care.

This concept of Contextual Safeguarding has led many safeguarding partnerships to reconsider their models of assessment, intervention, and response. However, as the framework gained prominence, the term ‘Contextual Safeguarding’ began to be used more broadly – and inaccurately – to describe any response to risk outside the home or extrafamilial harm, rather than recognising that it is a distinct approach requiring a commitment to whole system change.

Even when that commitment is made, meaningful implementation requires intense and sustained change management to move beyond surface-level compliance.

This is not simply a structural shift – it’s a cultural and operational one. It demands that practitioners and organisations actively reflect on their own positioning and practice, move beyond case-by-case thinking, and commit to creating safety within the spaces where young people live their lives.

One of the greatest challenges to implementing a contextual safeguarding approach lies in confronting the professional habitus – the deeply ingrained dispositions, assumptions, and practices that shape how practitioners interpret risk, assign responsibility, and construct interventions.

Without conscious effort to challenge these default settings, even well-intentioned practitioners may revert to familiar, individualised approaches that fail to address the social and structural dimensions of harm. For it to be effective, practitioners must be willing to share power, think beyond individual cases, and design interventions that reshape the environments around young people, not just their behaviour within them.

Learn more about Contextual Safeguarding from Professor Carlene Firmin herself, in her below video prepared for SAIL.

Contextual safeguarding – Useful Links

London Borough of Redbridge – Family Help – Contextual Safeguarding

Summary of project: A specialist exploitation team supporting Redbridge children and young people at risk of or having experienced criminal, sexual or other forms of exploitation outside the home.

Key Contact: Catherine Worboyes, Assistant Director, Children’s Social Care catherine.worboyes@redbridge.gov.uk

Read more about this project

Team: Specialist Exploitation Team (SET) – Sabina Samad, Head of Service, Siobhan McGeary, Service Manager, Family Help: Contextual

Safeguarding.

Partners: Frenford clubs, Box Up crime, Red Light Busking and Be Heard as One

Main Submission:

In Redbridge, we have recognised the unique needs of our children who are at risk of extra familial harm – the need for trusting relationships with professionals, to receive intensive specialist support and to be met where they are at and kept safe – and we have built a Specialist Exploitation Team (SET) to deliver this service and to keep young Londoners safe.

The SET is comprised of experienced specialist exploitation social workers who work directly with the child and their family. Through forensic analysis of referrals, SET ensures that only children who are experiencing exploitation are allocated to the team, ensuring caseloads are kept low – an average of six to eight children per worker. The combination of direct casework, manageable caseloads, specialist expertise and community partnerships, enables SET social workers to develop deep, meaningful, professional relationships with children and families, frequently spending time with them and focusing on establishing relationships and understanding their unique needs.

DeShawn* (not his real name) is one of hundreds of children who have changed their trajectory through working with SET and a voice that we would like to showcase and celebrate in this application. Subject to a child protection plan and transferred to Redbridge by another local authority, there were significant extra-familial harm concerns for DeShawn – he was just 15 years old, frequently missing and being heavily exploited through the drug supply trade. At the point of transfer, DeShawn and his parents were described as ‘hard to reach’ and ‘non-engaging.’ DeShawn was on the ‘edge of care.’ DeShawn was allocated to C, an experienced social worker within the SET. C was relentless in her approach to building a relationship with DeShawn, meeting him in places of his choosing

like community spaces, home and his alternative school provision. In the early weeks when DeShawn was arrested, C was the first to visit him in custody and attended each court hearing with him, gaining his trust by always showing up and being consistent. Amidst the crises, C made sure she was not just learning about the risks to DeShawn, but who he is as a person – what makes him happy, what he fears and what his hopes and dreams are.

As his trust with C grew, DeShawn developed the confidence to access the specialist interventions that SET have to offer. DeShawn accessed and continues to access the SET’s weekly Engagement Groups. These groups are designed to be as accessible as possible for children experiencing extra-familial harm – they take place after hours, are run by SET social workers and offer a safe community for vulnerable young people to build trusted relationships with safeguarding professionals. The Engagement Groups also bring different services to the young people – including careers, sexual health and drug and alcohol services to name a few – which has been particularly successful in engaging young people with services they may not ordinarily seek out.

Through innovative interventions, SET draw on a range of partners and community resources to build bespoke plans that divert children from harm and risk. This can only be achieved by investing time in getting to know them but also cultivating relationships with partners. C quickly identified that DeShawn’s passion is music; he is an incredibly gifted lyricist and when he performs, his whole demeanour changes.

Knowing this, C was able to engage DeShawn with the Red Light Busking service, a community service diverts vulnerable young Londoners from harm through music. DeShawn was supported to participate in this programme, receiving guidance around his music and spending time recording in a music studio, provided by one of our community partners with whom we work closely to provide a safe space and positive activities for young people open to the SET.

SET recognises the importance of role models, and in DeShawn’s case the importance of him having relatable role models with experiences that he could relate to. C drew on another SET resource, Be Heard as One – a specialist mentoring service. Here, DeShawn was allocated a male mentor with personal experience of criminal exploitation, gang affiliation and the criminal justice system. The mentoring relationship with this professional was pivotal for DeShawn. Connecting DeShawn with somebody who shares elements of his lived experience and speak truth to him about the journey he is on, is incredibly powerful means of connecting with him.

SET ensure that children have realistic options that meet them where they are at, a critical element of deterrence from criminal exploitation. Through tireless relationship-based work, they seek to understand the push and pull factors for extrafamilial harm on an individual basis without trying to make the young person fit a mould or pathway. In DeShawn’s case, this meant listening to his experiences of being excluded from mainstream school and being unsuccessful in his GCSEs and looking at what his other options were.

DeShawn’s life looks remarkably different from before his work with SET. He has never refused to see his social worker – he actively seeks her out; he chooses to attend the weekly Engagement Groups; he no longer goes missing and his contact with the police has been infrequent; he has a part-time job at McDonalds and is getting ready to make a music video. The SET approach has led to a positive engagement from DeShawn’s parents, who now attend all meetings with the local authority. The risks to DeShawn have reduced so significantly, he is no longer on a Child Protection Plan.

In our commitment to building safety for young Londoners, Redbridge recently launched its new Contextual Safeguarding Service. At this launch, DeShawn stood in front of a crowd of over 100, including council leaders, community partners and the Department for Education. He performed a song he had written about his experience of SET, so confident that he was barely recognisable from the young person we started working with. His performance was nothing short of incredible, and he received a standing ovation.

DeShawn’s is one story, of which there are many, about the creative ways in which Redbridge is building safety for young Londoners

Supporting Information:

BIZZ – ASPIRATION STATION AUDIO

Transitional safeguarding – co-produced with Dez Holmes, Director of Research in Practice

Transitional safeguarding is a term coined by Dez Holmes, Director of Research in Practice, in 2018 which describes an approach to safeguarding adolescents and young adults across the life stage between mid-teens and mid-twenties. The development of this approach has particular importance because of the disconnect that occurs between how we safeguard under eighteens and over eighteens, where there are completely different systems, different legislation, different eligibility criteria.

Transitional safeguarding is not only about those who are making a transition between services, it’s about the whole of the young people in our area having a smooth and positive transition into adulthood, preparing them for healthy, happy, safe adult lives.

In her video prepared for SAIL, Dez Homes gives a brief overview of transitional safeguarding and shares her aspirations and encouragement to practitioners and service leaders in London to seize the opportunities to shape systems which give young people the best chance of making a smooth and safe transition to adulthood.

In the accompanying video from Sara Rahman you will hear how services are being shaped in Lewisham, as a pathfinder for the Families First reforms, to give their young people the best support as they move into adulthood, informed by the transitional safeguarding principles outlined by Dez.

Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames & London Borough of Richmond (Achieving for Children) – Transitional Safeguarding (violence and exploitation) – VASA

Summary of project: Community safety and violence reduction approach to transitional safeguarding, to support adolescents transitioning into adulthood where there are ongoing concerns around violence and exploitation.

Key Contact:

Roberta Evans, Associate Director Family and Adolescents

roberta.evans@achievingforchildren.org.uk

Stephanie Royston-Mitchell, Community Safety and Resilience Principal – Safer Kingston Partnership

stephanie.royston-mitchell@kingston.org.uk

Read more about this project

Team: Multi-Agency Response

Partners: Contextual Safeguarding Leads, Leaving Care, Targeted Youth Support, Your Healthcare (community health provider), SWL St Georges Mental Health Trust, Substance Misuse Team, Adult Social Care, Virtual School, Housing, voluntary and community sector services e.g. Refuge, Crying Sons and Rescue and Response

Main Submission:

Kingston and Richmond Safeguarding Children’s Partnership (KRSCP) identified a gap in provision for young people transitioning into adulthood, when there is a

medium to high risk of violence and/or exploitation. Safeguarding Adult Review (Slyvia SAR) highlighted transitional safeguarding issues were not fully understood, resulting in significant gaps in the service the young person received.

KRSCP, Kingston Safeguarding Adults Board (KSAB) and Community Safety Partnership (CSP) committed to improving the transitional safeguarding response

and agreed as a shared priority. Through effective systems leadership, we have led the way on this work, driving change and innovation. We have inspired practitioners to develop a shared understanding of transitional safeguarding, develop creative solutions and improved collaboration to safeguard our most vulnerable adolescents.

A Multi-agency task and finish group, chaired by the Associate Director Family and Adolescents, reviewed the multi agency response, pathways and support offer for adolescents transitioning into adulthood. Identified:

Children’s safeguarding and support usually end at 18, but experiences of harm and trauma during childhood, youth and early adulthood may continue to affect

people across the life course, with unmet needs requiring complex (as well as potentially costly) interventions later in life. For example some of our young adults

are causing harm or exploiting others, they are our future parents and/or present later as adults with multiple and complex needs.

Unmet needs for young people transitioning into adulthood where there were ongoing risks of violence and/or exploitation, particularly if they experienced poor

education pathways, substance misuse issues, mental health, family breakdown, or criminal justice processes.

Several panels oversee different groups of vulnerable adults, but not one fit-for-purpose to support those with ongoing risk of violence and/or exploitation, as per the London Child Exploitation Operating Protocol 2021.

VASA protocol developed and includes the referral pathway and Terms of Reference for the VASA Panel, which oversees referrals for young adults with

continued significant risk and whereby a problem solving approach can be applied alongside the additional resources available.

A bespoke budget for the VASA panel, ensuring that the young person was at the centre of the support plan and involved in decisions around the type of support that would best help them.

Exploitation Training programme delivered to build professional’s confidence in responding effectively to exploitation.

Additional investment for 2024-26 includes:

● 18+ Missing and Exploitation Worker and Contextual Safeguarding Lead (£45K)

● Crying Sons Community Outreach (£50K)

● VASA Coordinator (£20K)

● Bespoke budget for VASA panel (£10K)

Exploitation training ensured participants gained a comprehensive understanding of exploitation dynamics and transitional safeguarding. By adopting a whole

system approach, attendees learned how collaboration between various stakeholders is essential for effectively identifying, preventing and addressing exploitation. Attendees were equipped not only to recognise, prevent, and address exploitation risks but also to contribute to disrupting and dismantling exploitation networks.

VASA Panel

66 referrals, mostly from Achieving for Children (AfC) as part of the transitional step-down/exit plans. Consistent for the past two years, showing the importance of

the panel.

65% of referrals are for males, mostly at risk of criminal exploitation. Females most likely to be at risk of sexual exploitation or all three (sexual exploitation, criminal exploitation, high harm).

44% of cases have substance misuse and mental health concerns, heightening levels of vulnerability and exploitation. Housing emerged as the most impactful factor, with 30% of cases experiencing a two-level reduction in risk. Crime and exploitation risk levels showed stability and 30% seeing a reduction by one level.

The panel has been instrumental in supporting case workers to understand risks they may not have previously understood. Minimal increases in risks, with 26% of cases affected. Among these, relationships with others and mental health were the most common areas of concern. Panel discussions played a crucial role in identifying areas where adolescents needed support, uncovering needs that were not initially recognized by the referring agency (65% / 14 cases).

Commissioned Research in Practice to review our transitional safeguarding approach to ensure continuous improvement. This presentation outlines the work. A report will be completed by Research in Practice which will assist us in further developing best practice and mainstreaming this work.

Dez Holmes (Research in Practice) has provided the following feedback:

To my knowledge, Kingston are the first local area in the country to use the community safety and violence reduction agenda as the vehicle to develop their Transitional Safeguarding approach. This has been a hugely exciting opportunity for Research in Practice to learn alongside Kingston colleagues, and we have been delighted by the positive engagement of professionals across all key agencies.

By building on strengths, including the well-established VASA panel, this project aims to refresh and embed an understanding of Transitional Safeguarding across the partnership. Through focus groups and workshops with multi-agency colleagues we have heard first-hand how committed local professionals are to ensuring all young people can be and feel safe as they make their journey into adulthood. It is a privilege to be supporting this kind of innovation.

Voice of the child

Our young people told us:

- “Not much in the way of expectations, being in various other countries that are useless. I hoped I’d get some kind of support but didn’t know what that would look like and I didn’t expect as much support as I got “

- “Getting financial support with food vouchers which has been really helpful and they were really quick in responding and would always grant the application.”

- “All round great support and a massive help to me. Fast response times and very supportive in terms of other help such as mental health referrals.”

The model is transferable to other boroughs as it focuses on systems change, using existing resources. Our transitional safeguarding approach has demonstrated that a small amount of investment has made a significant difference to the outcomes for some of our most ‘at risk’ young people as they transition into adulthood and who would not have had access to any support.

Supporting Information:

VASA protocol

Research in Practice Overview

Sylvia SAR

Feedback from professionals:

“Initially it felt a bit tedious, with the referral to be completed and having to wait for the panel. This was probably because I was after a “quick fix” for my young person. Once I became part of the process, it all made more sense and why things are done the way they are. So it has been a learning process for me. The support has been excellent and those I have been involved with have been very helpful.”

“I feel it was helpful to have lots of practitioners around the table to seek their views in a way that I may not have reflected on, as we all come from different perspectives and areas of expertise. “

“A big thank you to all those that helped my young person feel safer and strong enough to make a disclosure that hopefully has taken him away from some very dangerous people.”

Transitional Safeguarding – Useful Links

Developing racial equity in adolescent safeguarding

Introduction to disproportionality adolescent safeguarding

Virtually every corner of the adolescent safeguarding landscape displays disproportionality in outcomes and experiences by race/ethnicity. This inequity, at the most extreme end, costs young lives.

For many more, it results in an intersecting web of serious harm, potential unfulfilled, and cost to individuals and systems.

Put simply, every aspect of our adolescent safeguarding practice needs to highly attuned and responsive to racial inequities – this is not only the ‘right’ thing to do, but also the only way of being effective in our safeguarding practice.

Some data snapshots

The data on racial disproportionality in adolescent safeguarding is comprehensive, unarguable, and impossible to replicate here in full. Some illustrative data sources and statistics are as follows:

Homicides

Data from the Home Office Homicide Index 2019/20 – 2021/22 shows that Black males between the ages of 13-29 are 13 times more likely to a victim of homicide than similarly aged White males. This disproportionality becomes even more extreme the younger the population analysed. In London, 44% of the victims of teenage violence are black males, with this increasing to 73% when homicides are looked at in isolation..

The Homicide Index analysis doesn’t mince its words:

‘the inequitable risk of homicide faced by Black boys and men aged between 10 and 29 years of age should be considered a public health problem that requires urgent and sustained attention’.

Care, Youth Justice and Ethnicity

Two reports taking different approaches illustrate disproportionalities relating to the intersection of these factors:

ADR UK’s analysis of over 2.3 million children born between 1996 and 1999. This research finds severe disproportionality in the number of children in care having youth justice involvement (compared with their non care experienced peers), that the gap in involvement widens over time, and that they received proportionately higher numbers of custodial sentences. All these disproportionalities were further enhanced for certain ethnicities, notably Black Caribbean, White/Black Caribbean, White/Black African, Gypsy Roman, and Irish Traveller. Custodial sentences were twice as common among Black and Mixed ethnicity care-experienced children (9% of those in care) compared to White care-experienced children (5%).

HMIP’s 2021 thematic report into ‘The experience of black and mixed heritage boys in youth justice system’ looks in detail at the experience of 179 children across 9 youth justice services. There is nuanced and important analysis in the report, a key conclusion being that:

‘Addressing ‘disproportionality’ has been a longstanding objective in most youth justice plans, but our evidence indicates that little progress has been made in terms of the quality of practice. At a strategic partnership level there is a lack of clarity and curiosity about what is causing the disparity and what needs to be done to bring about an improvement.’

A further piece of key analysis points to the failure to meet needs upstream:

‘the large majority of black and mixed heritage boys in the youth justice system had experienced multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and had high levels of need, such as special educational needs (SEN) and mental health difficulties, which had not always been identified or properly addressed until they came into contact with the YOS. This raises questions and concerns about the support they received from mainstream services before their involvement with the youth justice system.”

Importantly, the report also makes a series of recommendations for YOSs and wider systems around what must happen to increase racial equity.

Some data snapshots – Useful Links

Why achieving racial equity feels hard and what we can do

It can seem impossibly difficult to tackle such a deep and intractable issue. The drivers of racial disproportionality in adolescent safeguarding are complex and wide-ranging, with roots that stretch back far upstream – for example into education, early years, and maternity settings (and further).

We have consciously chosen to refer to our ambition for ‘racial equity’ rather than ‘anti-racism’ to reflect some of this complexity.

Racism, both individual and systemic, is clearly a key driver of disproportionality and must be called out when encountered (as an example, Baroness Casey’s 2023 review of London policing clearly does this 3). However, racism intersects with wider inequalities, for example of income, health, housing, education, geography, as well as other protected characteristics.

Setting out to tackle ‘racism’ is essential, but also insufficient if done in isolation. We need to understand and respond to its intersection with other inequalities and causal factors. The following short paper, set in a health rather than adolescent safeguarding context, explains intersectional inequalities helpfully and reminds us that public health is a good prism through which to see adolescent safeguarding.

The second reason for referring to ‘racial equity’, rather than ‘equality’, is the recognition that historical and systemic factors create different starting points and therefore require different types of response. ‘Equity’ requires us to be proactive, allocating support and resources as needed to overcome disparities and achieve fairer outcomes.

So, given its intractable nature, how do we set about working towards racial equity in Adolescent Safeguarding? As good a starting point as any is the principle that ‘it starts with me’. This approach, borrowed (and slightly adulterated) from the Australian Human Rights Commission and NHS pledges on tackling racism, achieves several things. Firstly, it encourages self-reflection, an examination of the biases we hold and our own racial equity ambitions. Secondly, it makes our ambition manageable, with a focus on our own sphere of influence. Thirdly, it recognises the systemic nature of racism and disproportionality, and that if each part of the system (including each of us) can make change happen within its sphere of influence, then the collective effect is extremely powerful.

The systemic nature of racism and disproportionality means that any response must play out multiple levels. Within our own services this means at practitioner, team, senior leader and organisational levels. Across our partnerships, this means a shared understanding and response to racial equity from safeguarding partners. Scale of response is also key, with strategic co-ordination needed across Local Authority, Sub-Regional, Regional and National structures. Research also reminds us to look outside of the immediate adolescent safeguarding sphere into upstream services in social care, health, and education – something that is essential if we are to make a difference at scale. Finally, we must be attuned to, and actively influencing, political and social climates, which will ultimately have a major, perhaps the defining, impact on efforts to secure racial equity.

In this ambition, a torch is shone by the best of existing practice. What follows is not exhaustive, but a sample of approaches with proven impact and by experts in the field.

Why achieving racial equity feels hard and what we can do – Useful Links

Resources and existing practice

The Association of London Directors of Children’s Services (ALDCS) Racial Equity And Leadership Programme was established in 2020, initially as a direct response to the ethnic disproportionality in senior leadership within London’s Children’s Services.

The programme commissions leadership programmes to support the development of the black and global majority workforce, as well as supporting organisations and senior leadership in cultural competence activities.

Over time, the scope of the programme has expanded, recognising that the experiences of children, families, communities and the workforce are intertwined, and ALDCS REAL principles are ‘baked in’ to each of its five priority workstreams (one of which is Adolescent Safeguarding).

You can find out more about ALDCS REAL activity here.

In the below video filmed at the launch of the R.E.A.Lising Potential programme, Bev Hendricks, the Executive Director for Children, Lifelong Learning and Families in Merton and DCS Co-Lead of the ALDCS Racial Equity And Leadership (REAL) programme, shared a powerful message about leadership, purpose and racial equity.

Hackney – Anti-Racist Practice in Youth Justice

Hackney’s Anti-Racist Practice Standards have had major impact within the Local Authority as well as being drawn on by their peers. Recognised by Ofsted as ‘sharpening workers’ focus on anti-racist practice, and helping them better understand the needs, trauma and systems that affect children and their families’, the LA has also shared the trauma and learning from the Child Q strip-search, which is of particular relevance to adolescent safeguarding attitudes and practice. Also of note is Hackney’s youth justice prevention and diversion work, a critical ‘upstream’ space for developing racial equity.

https://www.younghackney.org/advice/staying-safe/child-q/

London Borough of Hackney – Improving youth voice and the understanding of the lived experience of young people coming into contact with the Police and Youth Justice system

Summary of project: The Prevention and Diversion Team’s child-first, systemic, anti-racist, restorative, and trauma-informed approach Improving outcomes for children at risk of entering the Youth Justice System

Key Contact: Lisa Aldridge, Head of Safeguarding and Quality Assurance

Read more about this project

Team: Prevention and Diversion Service, Early Help and Prevention

Main Submission:

Hackney’s Youth Justice Board Good Practice Grant funds the Prevention and Diversion Team within Young Hackney. This team provides Out-of-Court Diversionary interventions (OoCD) for young people aged 10-18, working with various agencies to address the complex needs of these children.

Over 80% of the children in the cohort are Black and Global Majority, often facing complex, traumatic family situations like domestic violence, parental mental health issues, substance misuse, SEND needs, and school exclusion, frequently in the context of systemic racism.

The team’s child-first, systemic, anti-racist, restorative, and trauma-informed approach has been successful in engaging children and building strong relationships. Additionally, the Involvement of residents aged 19-25 in Out of Court Joint Decision (OoCD) Making Panels has helped build trust within the community. The P&D team’s commitment to anti-racist and anti-oppressive practices is evident in their assessment process, which allows for open discussion of experiences of racism and discrimination from children and families’ perspectives and enables practitioners to advocate alongside and on their behalf. The collaboration with Speech and Language Therapists and the establishment of a Youth Justice Health Huddle have further improved the support provided to young people. If the SaLT therapist identifies any potential communication triggers, they immediately inform the judge, which has proven to be a significant asset to the YJS. Additionally, when a young person known to the YJS has communication needs, SaLT makes themselves available in court. Their presence, along with their engagement with parents, is making a marked difference in young people’s experience and outcomes. The HMiP Joint Inspection Report (May 2023) highlighted this approach as an area of outstanding practice.

Outcomes show that diversion from the formal YJS is effective, over the last 7 years we have had fewer than 1 in 5 children go on to enter the formal Youth Justice System after receiving our diversion support. Over 80% do not go on to become First Time Entrants within the following 18 months (82%-86% of children receiving a Triage Disposal). Importantly, despite what the Lammy Review found in 2017, Black and Global Majority children are volunteering to engage in Hackney’s offer (this cohort is over-represented in the makeup of our work) and there is strong evidence that they achieve the same positive outcomes as their White counterparts. Research from Middlesex University (2023) also indicates that ethnic background does not affect outcomes once children are referred to

P&D.

Feedback from children and parents

Parent: “(Worker), where do I begin? You worked with us once and I was happy. You worked with us for a second time and I was even more happy. You have changed our lives. The biggest thing was our home, we lived there (hostel) since we moved to the UK and never thought it would happen for us, but you always make it happen. Then (Child) and his education. I am speechless, thank you for everything”.

Parent: ‘’I was very pleased with the level of support offered to my daughter, stating that, though it is a shame something bad had to happen, (child) was able to work with a department that was able to help her in ways I could not, your communication with both schools and with other workers and to then report back to me was helpful to knowing (child) progress, so thank you for that”.

Child: “It was needed, as if this didn’t, who knows what further trouble I could have got into. I would have never done the victim stuff, which has really helped me to be a better person. So, yeah, I think more people should do this. I am definitely not as distracted as I was before, I feel like I have grown, doing that stuff with the email (restorative justice), I know I did wrong, but I have done something positive from it. You gave me feedback, printed the document for my Mum and you sent screenshots to my Mum, telling her about my hard work and then today, (victim worker) joined to tell me how positive and impactful my efforts were in giving the victim something. All this stuff has helped me realise and focus on what’s important, ME.”

Child: “I’m so much calmer now, I actually felt like I might be going crazy before so it was a big relief just to talk to someone about it. Do you know that I never mentioned those things to a single person before? You guys came at the right time for me – regardless of getting in trouble for the knife, I just needed to talk to someone. Yeah I’m calm now and I won’t get in trouble again. I know that things are normal and it happens to everyone, and I know how to relax my brain now! I do need a job though and I’ll keep applying and I’ll talk to the lady from Prospects, and I’ll have another try with Supporting Families if you tell them to contact me

again as well. Thank you for helping me, I definitely won’t pick up anything like that again, It’s not worth it. Thank you to the guy (clinician) as well.”

Next Steps

We have a project pending approval within our CE police locally to reduce the numbers of Black and Global Majority and White children who appear in court for low level offences following a ‘no comment’ interview. This proposes using a Deferred Prosecution offer (or Outcome 22 on the police record) made by Hackney YJS to the child, their family and their defence team.

Lewisham – Anti-Racist Strategy

Lewisham’s anti-racist strategy and practice is another flagship example within the sector, featuring in case studies by Research in Practice and CYP Now. Like Hackney, it is striking for its breadth of ambition, both for workforce and children and families. Of particular relevance to adolescent safeguarding is its TI –AR- RA (Trauma Informed, Anti Racist, Restorative in Approach) model, and the scale of its ambition in its partnership work, including safeguarding partnerships and with schools.

London Borough of Lewisham – Children’s Services: anti-racist practice framework

Summary of project: To support staff who work in Children’s Services to feel safe and allow them to challenge any attitudes or beliefs that may be discriminatory on the grounds of race at work or with partners or families

Key Contact: Kiren Ali, Media and Campaigns Officerkiren.ali@lewisham.gov.uk

Read more about this project

Team: Workforce Development and Senior Leadership Team in Lewisham Children’s Services

Main Submission:

The anti-racist practice network group was a group set up by Karen Morgan, Group Manager, as a response to the murder of George Floyd to address concerns that the black and ethnically diverse staff had around raising issues of racism and discrimination in the workplace and within the work they do with children, young people and families. Karen wanted to create a safe space where anyone who was concerned about racism and discrimination in Children’s Services can meet with others who can share and voice their problems and can receive support and guidance if there is a particular issue or grievance

they are dealing with.

From the establishment of the anti-racist network group a whole framework was developed by Karen Morgan, Sara Taylor and Julia Stennett around ‘anti-racist practice’ in Children’s Services that became integral to the ethos and the way Children’s Services wanted to operate with each other and with families and young people they looked-after. It was also championed and supported by the executive team with Director of Children’s Services Lucie Heyes and Pinaki Ghoshal, Executive Director of the Children and Young People’s Directorate.

Complementing the grass roots approach was also a focus on leaders so that when staff came to managers and leaders to raise their concerns an appropriate response was initiated, and it wasn’t simply brushed under the carpet because it felt ‘too uncomfortable” to deal with. Senior leaders knew that to deal with the issues effectively they have to be shown to take a lead to deal with issues raised by staff. The senior leadership team (SLT) in children’s services all received training on racism and anti-racism leadership from the Tavistock to ensure that they can deal with the issues raised at the group.

Initiatives that have been taken on the approach to anti-racism include:

- Establishing the anti-racist network – creating strategy, framework, statement, action plan with clear goals and outputs within timeframes

- Anti-racist training from Tavistock with the senior management team on what racism is and how it manifests, impacts and causes trauma with workforce, children and families

- Creating open space for black and non-white colleagues to have a safe space in which they can express their thoughts, feelings, experiences of racism that can be challenged if necessary

- Creating thinking spaces/reflective work around impacts of racism and trauma related to racism

- Sessions work on terminology around race and how it is used

- Workforce mentoring and the impact and experiences of trauma that they may be carrying

- Embedding anti-racist practice across all aspects of social work including the Signs of Safety Framework

The Ofsted inspection showed the good work that has been done in this area. They were particularly impress with it, saying, “The exemplary anti-racist practice network and safe space platform has positively supported staff from black and global majority backgrounds.”

The leadership in Children’s Services was particularly praised by Ofsted to drive cultural and

organisational change using anti-racist practices and embedding into all aspects of work done in Children’s Services, so that staff feel safe to practice and say things knowing they won’t be judged and it will be taken seriously and any aspects of racism or discrimination towards staff, families or children will be challenged.

This work is ongoing and is part of long-term strategy which is something that is of primary importance to the leadership, especially as the workforce is made up primarily of black and non-white staff.

Survey questionnaire results from CYP staff from March 2024:

•87% are aware of Lewisham Children’s Social Care work to promote anti-racist and anti-discriminatory practice and working conditions

•72% describe Lewisham as an anti-racist and anti-discriminatory department which promotes inclusivity for all

•76% feel they make a positive difference in their families’ lives

Supporting Materials:

Research in Practice article published article written on anti-racist practice and approach in Lewisham’s Children’s Services

CYP Now interviews with Pinaki Ghoshal on anti-racist practice in Lewisham Council’s Children’s Services

https://www.cypnow.co.uk/content/best-practice/local-spotlight-lewisham-council

https://www.cypnow.co.uk/content/features/making-children-s-services-leadership-more-diverse

London Borough of Haringey – Stop and Search Safeguarding Project

Haringey

Haringey’s Stop and Search project is an example of a project that began at pilot stage and has grown to become a key regional driver of partnership safeguarding practice. Launched in partnership between Haringey and their BCU, the project screens stop and search incidents for safeguarding concerns, sharing information and linking children with support. The project has now spread to 29 Local Authorities and 12 BCUs

London Borough of Haringey – Stop and Search Safeguarding Project

Summary of project: The project aims to consider the information obtained by the police in using their power of stop and search and, where there are wider safeguarding concerns, how these young people can benefit from timely support and interventions.

Key Contact: Sarah Ayodele, Safeguarding Project ManagerSarah.Ayodele@haringey.gov.uk

Read more about this project

Team: Stop and Search Safeguarding Project

Partners: Metropolitan Police Service North Area BCU, London Innovation and Improvement Alliance (LIIA)

Main Submission:

Stop and Search through a Safeguarding Lens

Collaboration is the bedrock of effective child safeguarding. The London Borough of Haringey Children’s Services and the Metropolitan Police Service in North Area BCU have, since 2020, been working on a phased project to improve the safeguarding response to children who are stopped and searched. The project aims to consider the information obtained by the police in using their power of stop and search and, where there are wider safeguarding concerns, how these young people can benefit from timely support and interventions.

The learning from this project has been invaluable and has informed changes to systems and processes in Haringey including adjusting the screening within the Multi Agency Safeguarding Hub and requesting individualised child stop and search data to enhance risk prevention plans via Multi Agency Child Exploitation meetings.

Together with London Innovation and Improvement Alliance (LIIA) we are delivering this pan London project phase and have 29 Local Authorities and 12 BCUs participating. Galvanising the safeguarding body of professionals, we are working to strengthen the mechanism by which children at risk are identified through stop and search, how information is shared, and to ensure children are provided with better safeguarding support interventions. Our project builds on a child centred approach, serves to create safer communities and reduce trauma to children where this could occur. It aligns with the commitments made in a New Met for London and delivers on the priority set by the Association of London Directors of Children’s Services to build safety for young Londoners.

Racial Equity resources and existing practice – Useful Links

Extreme ethnic inequalities in the care system – University of Huddersfield

Safeguarding children from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities | NSPCC Learning

Safeguarding reviews silent on Black, Asian and Mixed Heritage children – GOV.UK

https://www.cypnow.co.uk/content/best-practice/local-spotlight-lewisham-council

https://www.cypnow.co.uk/content/features/making-children-s-services-leadership-more-diverse

Adultification – in development with Jahnine Davis, National Kinship Care Ambassador and Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel member

This section is in development with Jahnine Davis, National Kinship Care Ambassador and Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel member. For now we are sharing some key resources and foundational literature

Adultification bias:

“The concept of adultification is when notions of innocence are not afforded to certain children. This is determined by people and institutions who hold power over them. When adultification occurs outside of the home it is always founded in discrimination and bias. There are various definitions of adultification, all relate to a child’s personal characteristics, socio economic influences and / or lived experiences. Regardless of the context in which adultification takes place the impact results in children’s rights being either diminished or not upheld.” Davis and Marsh 2020

“Adultification may differ dependent on an individual’s intersecting identity, such as their gender, sexuality, and dis/abilities. However, race and racism remain the central tenant in which this bias operates” (Davis, HMIP 2022)

“This concept is where adults perceive Black children as being older than they are. It is a form of bias where children from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities are perceive, as being more ‘streetwise’, more ‘grown up’, less innocent and less vulnerable than other children. This particularly affects Black children, who might be viewed primarily as a threat rather than as a child who needs support” (from Child Q Child Safeguarding Practice Review)

“While research indicates Black children are most likely to experience adultification bias, it is important to understand the different contexts in which it can feature, which places all children at risk of this discrimination. However, this should not mean shifting a focus from Black children but instead a curiosity to understand how race/ethnicity and other aspects of a child’s identity compounds these different contexts” (Davis, HMIP 2022)

Adultification – Useful Links

Child-Q-PUBLISHED-14-March-22.pdf : Child Safeguarding Practice Review into the experience of a 15 year old girl strip searched by police at school, which is recognised as a high profile example of the damaging impact of adultification bias.

Child Q Update Report – Why was it me? – YouTube : a video delivered by Jim Gambol on behalf of the Hackney Safeguarding Children’s Board updating on progress one year on from the publication of the Child Q Child Safeguarding Practice Review.

Adultification bias within child protection and safeguarding: HMIP academic insights series report produced by Jahnine Davis.

cspr_lilo_-_june_2023.pdf This Child Safeguarding Practice Review was commissioned by Lewisham Safeguarding Children Partnership in respect of a Black British Caribbean male, ‘Lilo’, who died at the age of 17 in 2021. He died as a result of being stabbed, in the context of extra-familial harm. Adultification bias was found to be significant in the context of Lilo’s life.

Safeguarding children from Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic communities | NSPCC Learning

Boys to men: the cost of ‘adultification’ in safeguarding responses to Black boys in: Critical and Radical Social Work Volume 8 Issue 2 (2020): in this paper Davis and Marsh argue that in order to provide meaningful and effective support to Black boys, both the use of an intersectional lens and an awareness of adultification is necessary.

“It’s Silent”: Race, racism and safeguarding children – Panel Briefing 4: The national safeguarding children panel report analysing responses to race and racism in CSPRs (authored by Jahnine Davis).

Girls-in-the-YJS-webinar-Tues-10-June-2025-Slide-pack.pdf: Presentations including Jahnine Davis on adultification

Children in care and care leavers

“Care as a verb not a noun: care is something we do for children, not a place we put them”

Being in care can be protective against adolescent risk. High quality homes, whether foster care or residential children’s homes, can promote safety and well-being. The principles which underpin SAIL, which prioritise caring, trauma-informed relationships, that centre children and young people’s voice and participation, are also the principles which are most important in supporting the safety of children in care.

Those working to safeguard adolescents need to be particularly attuned to its intersection with being care experienced. Broadly speaking, this includes an awareness that:

- Children going into care will have experienced Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES). These may manifest in multiple ways (for example mental health/emotional wellbeing concerns, attachment difficulties, substance use, offending) each of which in turn may amplify the adolescent safeguarding risk.

- Children in care may have additional needs that are related to or alongside their ACES. As noted above, children with a neurodivergence or Speech, Language and Communication Need may be less able to communicate when exploitation or abuse is happening, and we have an opportunity for children who are being cared for to these ensuring these needs are supported and met where in some cases they may not have been. Working to understand what is driving a young person’s behaviour through careful and curious relational practice, and well-informed assessment is vital.

- Entering the care system may increase adolescent safeguarding risk. There is a shortage of placements for adolescents presenting complex needs, with some being placed in environments that struggle to keep them safe. One aspect of this, the placement of children away from their home area, is detailed in the 2019 APPG report No Place Like Home Another aspect may include increased exposure to other children/young people facing adolescent safeguarding risks, which has the potential for both peer influenced escalation and the removal of a safe home place from where to escape their concerns (even if temporarily).

- No Place Like Home also notes the loss of protective factors for children placed out of area. Placement geography is just one element of a wider loss of protective factors. Children in care may have less in the way of strong, potentially protective family relationships. Peer, educational, mentoring and other relationships may be disrupted, especially in the case of frequent moves. Children in care and care leavers also comment on their frustration at frequently changing professional relationships, including having to ‘re-tell my story’ of trauma or abuse.

- Some children will go into care specifically because of an adolescent safeguarding risk. Historically, children’s systems have not been a good fit for these children, with the child protection framework being designed for a younger age group. The emergence of specialist adolescent safeguarding services are a response to this, however the fit across child/adolescent and inter/extra familial harms can still prove clunky in terms of service provision.

- Children in care are more likely to go missing, and during this time may be at increased risk of grooming, abuse, or exploitation. In the case of care leavers, as young adults they are unlikely to be considered ‘missing’, though they may face the same risks.

- Perpetrators of exploitation are attuned to the vulnerabilities noted above and will specifically target children in care and care leavers because of them.

A note on Care Leavers

It is essential that all partners (and indeed society) recognise there is a need for adolescent safeguarding beyond a young person’s 18th birthday – please see the section on Transitional Safeguarding for more detail on this. It is also important to understand the specific position of care leavers within this cohort. The factors noted above for children in care remain relevant, yet the legislative framework and availability of professional support declines notably after an 18th birthday. A group already disadvantaged by their care experience (Independent Review of Children’s Social Care 2023), is expected to transition to adulthood earlier, and with less support and protection, than their non-care-experienced peers. Inevitably, this results in an over-representation of care experienced people amongst the population of young adults facing adolescent safeguarding risks.

Care Leaver status is defined by law and places duties on a Local Authority to provide support services until the age of 25. These ‘corporate parenting’ duties are due to be extended to other government departments and relevant public bodies through the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill (2025). This is a welcome development that, with sufficient focus, should enhance the multi-agency safeguarding approach to care leavers.

A group already disadvantaged by their care experience is expected to transition to adulthood earlier, and with less support and protection, than their non-care-experienced peers.

What does this mean regarding our approach to working with Children in Care and Care Leavers?

Those designing and working within adolescent safeguarding services will be aware of the increased risks facing children in care and care leavers. The principles of good practice encountered in SAIL are equally applicable to this cohort – with the proviso that some, for example the importance of strong relational practice – may be even more important for a cohort that can have less secure attachments.

Some areas warrant new or additional consideration, which is particularly timely as safeguarding approaches change in response to new legislation and national reforms. One such area is information sharing and the co-ordination of multi-agency approaches beyond the age of 18, and transitional safeguarding more widely.

There are two specific recent developments to be aware of in London:

- MOPAC’s Reducing Criminalisation of Children in Care and Care Leaver’s Protocol

Exposure to the criminal justice system has the potential to increase adolescent safeguarding risks. This partner protocol significantly strengthens its predecessor as well as offering stronger protections for care leavers. It includes recommendations for Local Authorities, Police, and Children’s Homes/Supported Accommodation that have strong crossover with Adolescent Safeguarding activity.

- Pan London Care Leavers Compact

The Pan London Care Leavers Compact is an ALDCS sponsored partnership led regional programme that seeks to improve care leavers’ experiences and outcomes. It brokers specific regional offers for care leavers (such as free prescriptions, council tax exemption and transport discounts), as well as making longer term improvements in four themed areas of housing, health, ETE, and criminal justice. All these areas strongly intersect with adolescent safeguarding, both in terms of risk (when they are inadequate) and in terms of protection (when they are strong). The find out more about this work please see the LIIA Care Leavers Priority Area.

Children in care and care leavers – Useful Links

https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/no-place-at-home.pdf

Resource

This LGA resource is aimed at councillors but provides an excellent source of information for anyone interested to understand the statutory duties and guidance in relation to children in care and care leavers.

Corporate parenting: Resource pack for councillors | Local Government Association

Reducing the criminalisation of children looked after and care leavers

Extract from the foreword by Kaya Comer-Schwartz, Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime

Ensuring every child and young adult in London has a fair and safe start in life is a responsibility we all share, and it matters most for children in our care and care leavers. I’m genuinely thankful to all the partners and young adults who have shaped the review of this Protocol. Your voices and your collaboration will help to drive positive change across London.

This updated version of the Protocol sets out a clear agenda to reduce the unnecessary criminalisation of children looked after and care leavers, featuring shared principles, and commitments across partner agencies. Ambitiously and importantly, it now includes care leavers up to the age of 25.

At the heart of the Protocol is the question ‘would this response be good enough for my child?’

Reducing Criminalisation of Children Looked After and Care Leavers | London City Hall

Reducing criminalisation of children looked after and care leavers – Useful Links

Girls and young women

Practice with girls and young women – by Abi Billinghurst, Founder and CEO of Abianda

The National Police Chiefs’ Council confirmed in 2024 that “violence against women and girls (VAWG) has reached epidemic levels in England and Wales.” [1] In the same year, 1.6 million women and girls over the age of 16 experienced domestic abuse [2]. One in four women have been raped or sexually assaulted since the age of 16 [3], and since 2009, one woman has been killed every three days – most often by a partner, family member, or someone known to them [4]. Young women aged 16-19 face the highest risk of domestic abuse compared to any other age group [5].

Sexual harassment and abuse are pervasive and normalised in the everyday lives of young women and girls. They report feeling unsafe in public spaces, experiencing harassment on public transport, on the streets, and in schools. This includes unwanted attention, leering, groping, touching, being rubbed against, and, in some cases, being forced into sexual acts in public.

Pornography has become mainstreamed, often depicting misogynistic and violent sex. Acts such as strangulation and the eroticisation of rape now permeate many young women’s experiences of sex and relationships. Meanwhile, a relentless tide of online misogyny and gendered violence continues to intensify.

Across different intersections of identity – race, class, sexuality, disability, and gender identity – experiences of harm can be unique, multi-layered and often exacerbated. [6][7][8]

Young women’s experiences are fundamentally different from those of young men, simply as a result of their sex. Recognising this epidemic and its distinct impact on girls means our safeguarding efforts must be viewed through a gendered lens. Just as gendered violence affects every aspect of young women and girls’ lives, our understanding, services and safeguarding responses should be integrated across all directorates, infrastructures and policy areas – not confined to a single one.

The reality is that the outcomes for young women and girls are directly influenced and impacted by the perception, response and understanding of professionals who may not take a gendered approach to their work or experience with them. VAWG doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it stems from a societal approach to women and girls – we need to understand and proactively look for nuance in the ways that young women’s behaviour manifests, or explains their experiences.

More bluntly, the fact that girls and young women are missing from offending, gang and knife crime data is critical. The distinctly different ways these issues affect their lives are rendered invisible, and as a result the systems and services built to address them are not designed with young women and girls in mind.

- How adolescent young women’s experiences of sexual exploitation have been consistently missed by professionals who have lacked the curiosity and mistaken the grooming, coercion and control that they experience, as them being complicit, ‘promiscuous’, and having sex with older men because they have ‘chosen’ to [9[10]

- The way that Black girls are subject to adultification which lessens recognition of their vulnerability, and results in less support or protection [11]

- The failure of statutory services to respond to the complex situations of girls and young women who come to the attention of appropriate adults only when the risk and harm is so acute that the system cannot respond quickly enough.

- The way that young women’s ‘survival behaviour’ is misunderstood, misinterpreted and often results in a punitive and criminal response from those who could help her. This might include angry and violent ‘outbursts’ in school, or when she’s not getting what she needs from services; engaging in risky sexualised behaviour as a way of avoiding further harm; bringing in friends and other girls as a way to divert harmful attention from herself; carrying drugs and weapons for partners, family or friends in the complicated context of her relationships.

Support for girls and young women

The importance of relationships in the lives of young women and girls should not be understated. Often a source of community, support and safety, relationships with people around them can play a key part in helping young women to build their resilience and tackle challenges (including where they feel unsafe to seek help from the police). However, relationships are often the key source of harm in young women’s lives, and the significance of relationships in their lives forms an important part of the complex drivers of offending, coercion, control and harm. Whilst the nature of relationships can shift from within the home, to outside of it, the fact is that they persist as a specific source of harm, and a key factor in their safety.

In the context of these specific and unique experiences, we can serve girls and young women best if we consider the principles of specialist work with them.[12]

Often this is about creating safe spaces (a term which will mean different things to different young women), but women-only spaces can offer a sense of safety. In these spaces we can support young women’s sense of power and empowerment in the context of trauma, addressing normalised and high levels of violence, supporting young women to master relationships, such are the important roles that they play in their lives. A focus on skills development is essential, including leadership skills, agency and self efficacy.

At Abianda we work to ensure young women develop independence and agency. Our one-to-one and group work programmes support young women to master safe, and consensual relationships, with peers and adults. We create spaces where they are supported to think critically across issues that affect young women in relation to criminal exploitation and violence, and for groups to develop a collective and new narrative about young women’s experiences that moves away from the pathologising individual experience, and towards a collective understanding of the gendered and intersectional experiences of girls and young women.

This, along with critical thinking, are vital skills for young women in being able to navigate relationships, spaces and systems as safely as possible, and so they can understand and advocate for their own needs in systems that are often not designed for them.

We adhere to the principle that we cannot just work with individuals to bring about lasting and sustainable change, but that we must take an ecological approach. This means working in the spaces and places to increase safety using principles of contextual safeguarding ; we endeavour to bring about practice and service change through our national training programmes; and, working alongside young women with lived experience to influence policy and wider systems change

Other specialist work with girls and young women

- Agenda Alliance: a brilliant source of research and learning, they advocate and campaign for systems and services to respond appropriately to women and girls with unmet needs.

- Advance, women’s organisation, delivering systems change and trauma and gender-informed community-based support for women and girls affected by domestic abuse, including those in contact with the criminal justice system. Advance and partners, deliver the Maia and Lift Project across eight London boroughs for girls and young women aged 9 – 25.

- Sister System: Rooted in race and gender equity, Sister System works alongside girls and young women aged 13-24 affected by care, offering early intervention mentoring and educational programmes.

- Daddyless Daughters: Provide physical and emotional safe spaces for girls and young women aged 11 – 25 years old, who have been affected by family breakdown, abuse and adversity

- Make Space for Girls: campaign for parks and public spaces to be designed for girls and young women

- Milk Honey Bees: Provides safe spaces for Black girls to flourish. Rooted in the creativity, celebration, and liberation of Black Girlhood, Milk Honey Bees also produce research and amplify the voices of Black Girls.

- Young Women’s Trust

- Girls Empowerment Team (Brimming YOS): An example of embedding girls work in local authority and youth offending systems. GET recognises and responds to the specific needs and vulnerabilities of girls who are at risk of offending,or have offended.

- LB Islington VAWG Practice and Development Team are doing some interesting and important work looking at the triangulation between childhood experiences of domestic violence, the use of violence in their adolescent relationships, and offending activity.

Girls & Young Women – Useful Links

Young women and neurodiversity

Males often outnumber females in diagnoses of autism, and there is a growing school of thought that suggests particularly with certain Neurodivergences such as Autism and ADHD, young women are often generally underdiagnosed. At the most extreme end, for some women these diagnoses only come after a period in hospital. There are lots of potential reasons for this, but it is important to consider when dealing with girls who may be being exploited that there may be additional vulnerabilities that have not been picked up and perhaps are less well supported than they might be in boys.

A significant concern from some young people, and parent/carers that we speak to is that neurodiversity and trauma are complex and have significant overlap in terms of symptoms. Really getting to know the young person and their network is important in working out how best to pitch interventions.

This page from the National Autistic Society explains more: https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/identity/autistic-women-and-girls

Practice with boys and young men – in development

This topic within SAIL is still in development with colleagues and partners and will be coming soon!

If you’d like to directly contribute to this section then we’d love to hear from you – whether it be providing written content, sharing research, resources being part of the ‘Talking Head Series’ – you can read more about the ‘SAIL talking head’ series here!

What to do when working with exploitation and harm through violence

County lines

Safeguarding – What to do if you are concerned

If you are concerned that a young person is being exploited then a referral to Children’s Services should be made. All concerns that a child may be at risk of, or experiencing, exploitation or violence must be referred to the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH), following standard referral protocols. Exploitation and harm through violence must be treated with the same urgency as all other forms of abuse.

Partnerships and multi-agency working